An introspective look: Cecilia Alemani in conversation with András Szántó

Cecilia Alemani

We are speaking ten weeks before the opening of the 59th International Art Exhibition at the Venice Biennale. What does a day in the life of a biennale curator look like in this moment?

You can see what my day looks like now, just take a snapshot on your computer. Me talking on Zoom all day long. From 7 a.m. to 2 p.m., I do Italian stuff; then I have three hundred email messages to process. Kidding aside, right now, after the press conference and the big announcement, this is a turning point. On the one hand, we are building the architecture of the show—a lot of hands-on stuff. On the other hand, we are finalizing the catalogue. Because of Covid, we must print it early. It’s crazy, and not much fun. I hope that by the time I am in Venice in March it will be a lot of fun.

When we first chatted about your theme for the Biennale almost a year ago, I was delighted to hear that you planned to focus on dreams—on futures, on hope, as I understood it. How did you arrive at this thematic territory? And how does it respond to our moment?

It was a convergence. At the beginning I started by reading a lot of artists’ writings. That is how I got the title. Then, from the hundreds of conversations with artists during these long years, something else emerged. The medium of Zoom created a format not unlike a confession. It wasn’t the classic studio visit, but more of a series of very personal, almost existential conversations. I was looking directly into people’s houses and lives. This intimacy and confessional approach influenced my thinking. The introspective quality of these conversations ended up informing the theme.

But—not having seen the show yet—the outcome still sounds life-affirming. How do you frame a somewhat positive message in a time of disruption, polarisation, and planetary crisis? How do you avoid a Doom Biennale?

That goes back to what the artists have to say. I have seen thousands of portfolios. I did hundreds of online studio visits. And seldom was the discussion about openly political or social issues. I saw very little on Covid. I saw few things about social unrest. I may be generalising, but I think at this moment many artists are returning to intimate modes and settings. They are looking inside, rather than outside. Artists are processing the trauma in a different way: less overtly and instead in a more introspective way. Whether the overall impression of the exhibition is optimistic or pessimistic, we shall see. Ultimately, this show is a celebration of art.

Specifically, you titled it The Milk of Dreams, from the surrealist artist Leonora Carrington, who lived much of her life in Mexico. One of her fellow surrealists, Alejandro Jodorowsky, wrote later that Leonora introduced him to tarot cards. There is a spiritual aspect to all this. What are we to make of these connections?

There is a lot of spirituality in the show, especially in the historical micro-exhibitions, which I call “time capsules.” One of the pillar themes is the “post-human”—inspired by authors such as Rosi Braidotti and Donna Haraway, who challenge the idea of the individual being at the center of the world. These ideas are about imagining other kinds of relationships, rooted in togetherness and symbiosis. I was looking at artists who were trying to break with the familiar polarities and dualisms that came out of the Enlightenment—mind and body, nature and culture, feminine and masculine, and so on—to imagine a world that is more fluid and in-between. That is where the occult and the spiritual come in.

Surrealism is in the air. It is almost a cliché to say we are living in a surreal moment. Fact and fiction have blurred. The Met just closed a huge and excellent show on the subject, “Surrealism Beyond Borders.” Are symbolism and dreams taking a more central role in contemporary art, if one can generalise, after so many years of conceptualism?

I think so. It goes back to this idea of taking a more introspective look not just to find refuge in the unconscious and the personal, but as a way of internalising the major issues and challenges of our time. To give you an example, the show has a section of works that deal with ecology and climate catastrophe. However, I tried not to go with more evidently documentary works. There are many artists who are already doing that in a really smart way. I was searching for artists who are exploring this very timely social theme but doing so in a more personal way—filtering it through their dreams and their unconscious.

Technology might be contributing to this aura of surrealism, and not only because it allows artists to create fanciful, out-of-this world imagery. The metaverse is a surreal universe in the strict sense of the word—we are escaping into another reality, or non-reality. Are such concerns around technology present in the Biennale exhibition?

One of the core themes of the show is the relationships between the individual and technology. One of the “time capsules” is dedicated to the cyborg, the union between human and artificial entity. Pre-pandemic, we were living in an era of technological optimism—we thought we could perfect our bodies, that we would live longer and longer—mixed with incipient fear of an artificial-intelligence takeover. I believe this polarised relationship with technology has now been turned upside-down. On the one hand, we have realized the fragility of our mortality, of our bodies in the face of an invisible force. And in that same moment, when we wanted to be together with family and friends, our relationships were being filtered through a computer screen. Technology kept us together and apart. This is a key concern for contemporary artists.

You are the first Italian woman to curate the Biennale. What took so long?

I wish I knew. Isn’t that incredible? One hundred and twenty-five years. What took so long causes terrible anger: a repressive, sexist, discriminatory system. But I don’t want to dwell on the past. It is a great honour that I was invited to do the show. Hopefully, I will do a good job and they will continue to invite women curators.

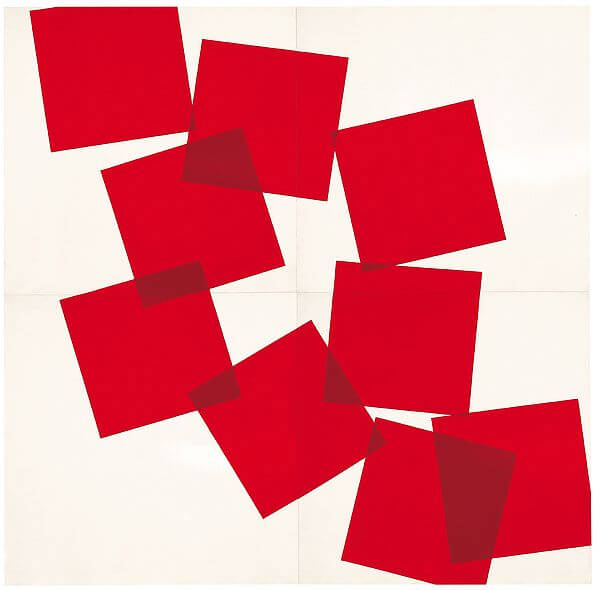

Reviewing the Biennale artist list, I appreciate your emphasis on artists who have had long careers. As a Hungarian I was pleased to see, for example, the New York–based Ágnes Dénes and Vera Molnár, the early computer artist, who is based in Paris. How do you see work by artists of various generations alongside one another?

I am interested in providing the audience with tools to read works in different way. What does it mean to look at a painting by Jacqueline Humphries next to a computer drawing by Vera Molnár? Is there something that this reading adds to each one? The idea is to create connections and bridges between the generations.

This is a huge Biennale. One thousand five hundred works. Two hundred and thirteen artists.

It’s bigger than usual, but not the biggest so far. However, eighty-four of the artists are in these small “time capsules,” while some of them are represented by a single work in a room. So the numbers are a bit misleading, because in terms of space the show will not feel overcrowded. There will be moments of focus, and other moments more common to the Biennale setting, with installations and the like. It’s a big number, for sure, but I hope it will not feel overwhelming.

Because of the postponement of the Biennale, you had more time to prepare. Were you able to use this to your advantage?

It was great, actually. How can I complain about having more time? My only complaint is that I got stuck in this little corner of my apartment staring at a screen for two years. I did one trip to Scandinavia, and that’s it. The historical presentations would not have been possible if one only had a single year. Museum loans take time. I was able to go deeper, with more research. The show could include other kinds of cultural figures as well. There is, for example, a literary thread running through the exhibition.

Each Biennale has its own curatorial methodology and process. Some are tightly focused, others more multidimensional. Some are linear, others associative. How would you describe your approach to the curation of the most important exhibition in the world?

I wanted it to be a focused exhibition, a thematic exhibition. There are lots of stories weaving through it—that is the beauty of the Biennale. One thing I knew was that I didn’t want to focus on creating a snapshot of the present. Ralph Rugoff did that in 2019, and I liked his show, because he captured a generation so clearly. But I couldn’t do that sort of show, especially during Covid. I wanted a show that would be clear to read, and trans-historical, bringing together multiple generations. And especially, I wanted to give space to voices that would not have been considered before—to create this sense of movement, looking back and forward.

You are from Milan, not far from Venice, but for Italy still a different place. After spending more time here, what do you think about the city now?

It was surreal to visit Venice in the pandemic. It was completely deserted. People couldn’t leave their houses. I think this brought to the fore some of the contradictions of the city. Now that it was empty, people complained about it being empty, whereas before, overcrowding with tourists was a huge complaint. Whatever the case, we saw a new side of the city, one that I hope never to see again. No, I didn’t see dolphins in the canal. But I did see clearer water.

By happenstance, Venice is perhaps the ultimate urban symbol of climate change. I remember people walking around in rubber boots during the last Biennale. How did that seep into your thinking about the kind of Biennale you would create?

I remember the last time I was in Venice before Covid was for the closing of Ralph’s exhibition, in November 2019. I remember the crazy high water everywhere, and yet still so many tourists—such a paradox. At that point, I think everybody expected I would do a show on climate change. Three months later, that idea was swept away by the pandemic. It obviously remains a very serious concern.

I suspect that by now you have uncovered Venice’s secrets. What advice do you have for the Biennale visitors when they need to take a break from the endless art? Is there a hidden gem or a particular area they should go discover?

For me, the biggest discovery after spending more time in Venice—I wonder if I should tell you this, though – is Sant’Elena, an area just behind the Giardini. It feels like a metaphysic painting by Giorgio de Chirico. The streets were built in the thirties, and they are mostly empty, creating an almost eerie atmosphere. But there are lovely restaurants, a new hotel, a lot of older people, and kids, even a playground. That was a pleasant surprise.

Finally, a decade or two from now, when people think back to the 59th Venice Biennale, what do you think they will most remember it for?

I think they will remember it as the Covid Biennale, the women Biennale, and hopefully the fun Biennale of rebirth and togetherness, after so many months of being apart.