An Interview with Seba Calfuqueo, Mapuche Artist and Activist

Seba Calfuqueo

MS In your artist statement, you say that your artistic practice, as a Mapuche and trans subject, is characterised by questioning the colonial binary order and its consequences in indigenous societies as well as global ones. What is the most difficult consequence of the colonial order, and how does this influence your practice?

SC For me, the greatest problem of colonialism is its continuity and its ability to perpetuate itself. One of the most significant consequences is the loss of indigenous languages. In my family, Mapudungun, our mother tongue, was denied and silenced by the weight of colonialism. Despite its absence in everyday conversations, it was always present in my close circle. After the loss of my grandparents, the last direct link to our roots, Mapudungun became an urgent need, a way to reconnect with my identity, my family, and my territory. I felt the responsibility to reclaim what was taken from us, to honour the memory of my ancestors, and to keep our culture alive. I started studying the language, learning its sounds, grammar, and rich worldview. Each word I discovered was like a treasure, another piece in the puzzle of my identity. Mapudungun stopped being a distant echo and became a powerful voice, a tool of resistance and healing. Today, I use Mapudungun in my work as a form of expression and reclamation. I integrate it into my paintings, sculptures, and installations to invite the viewer to reflect on the importance of preserving linguistic and cultural diversity. I also use it as an educational tool, encouraging others to learn the language and overcome the shame imposed by colonialism. For me, Mapudungun is much more than a language. It is a link to my past, a bridge to the future, and a way to honour those who fought to keep our culture alive. Through my art and my commitment to the revitalisation of Mapudungun, I seek to contribute to the construction of a more fair and inclusive future, where all voices are heard and valued. I believe another important part of this colonisation lies in the binary system that governs us, the separation into binaries and the belief that the world is black or white. In my work, I address these reflections, and rather than providing an answer, I see it as an invitation to question and explore the past in relation to our present.

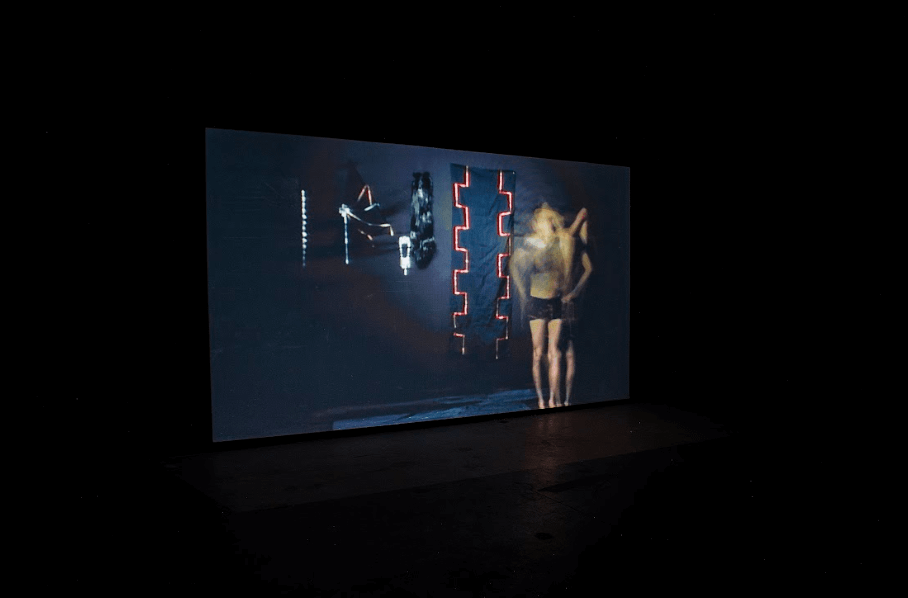

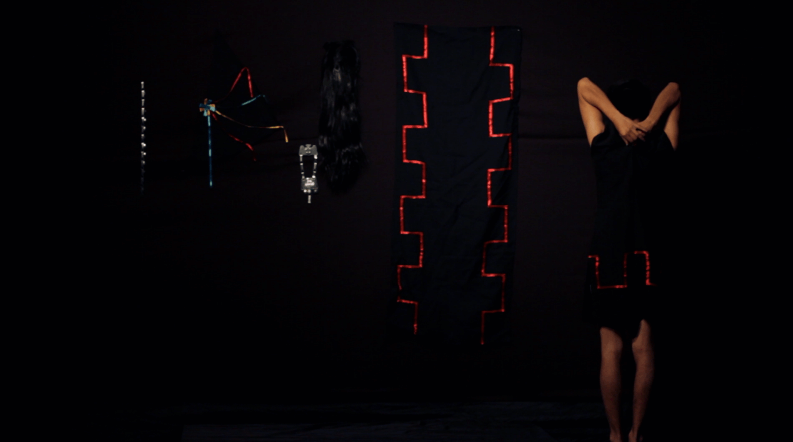

MS Could you tell us about the video performance “You Will Never Be a Weye” (2015) that you presented in the main section of the Venice Biennale curated by Adriano Pedrosa?

SC “You Will Never Be a Weye” is my first work, a video performance that I created in my final year of visual arts studies at the University of Chile. I recorded it in 2013 at the same school, in the performance workshop, but it was exhibited two years later, after a curator friend, Mariairis Flores Leiva, who encouraged me to show it in “Donde no habito,” one of my first solo exhibitions. She curated the exhibition, which took place at Galería Metropolitana, one of the most established independent spaces in Chile. The video performance narrates the story of the machi weye, a healer of the Mapuche community who was documented in various colonial chronicles, particularly in “Cautiverio Feliz” by Nuñez de Pineda y Bascuñan, written in 1863.

The healing practices of the machi, his way of dressing, and even his movements seemed to be a real problem for the construction of virility defended by the colonisers. According to the dictionary “Arte y gramática general de la lengua” by the Catholic Jesuit Luis de Valdivia, dating from 1606, the verb Hueyún is equivalent to the “nefarious sin” and Hueyútun to “the act of committing the sin of sodomy”. The dictionary “Arte de la lengua general del reyno de Chile” by Andrés Febres, dating from 1764, defines “hueye” as “receptive sodomite practices” and “maricón” (faggot). This latter term is also used as a synonym for coward and traitor. Finally, the book “La voz de Arauco, explicación de los nombres indígenas de Chile” by Ernesto Wilhelm de Moesbach, dating from 1976, proposes the term “Huelle” as “faggot and paedophile” and “Hue” as “place of sodomy”. The Jesuits stigmatised the weye as queers because they had receptive desires towards other men, wore skirts, and acted like women. The term “puto” was particularly problematic for Spanish colonial society, as it threatened traditional and untouchable values such as procreation, family, morality, and social order. They repudiated the acts of the weye because they were sodomites, people with inverted gender, effeminate, witches, and worshippers of the devil. It is important to note that the accusation of sodomy and idolatry did not fall solely on the Mapuche, as similar cases occurred in various peoples during colonisation. There is a colonial perspective that outright despises sexual practices that do not conform to Christian life.

The performance is exhibited in the “Disobedience archive”, an archive of dissenting voices on various topics; my core addresses issues around gender, particularly the construction of this concept since colonisation. Due to the imposition of Christian morality, the role of machi came to be assumed practically only by women. In the 4:46-minute video performance, my semi-naked body appears, slowly dressing in a machi costume that imitates what women wear. I say “imitates” because this costume is sold as a disguise in commerce, to which I add fake jewellery with and a synthetic wig.

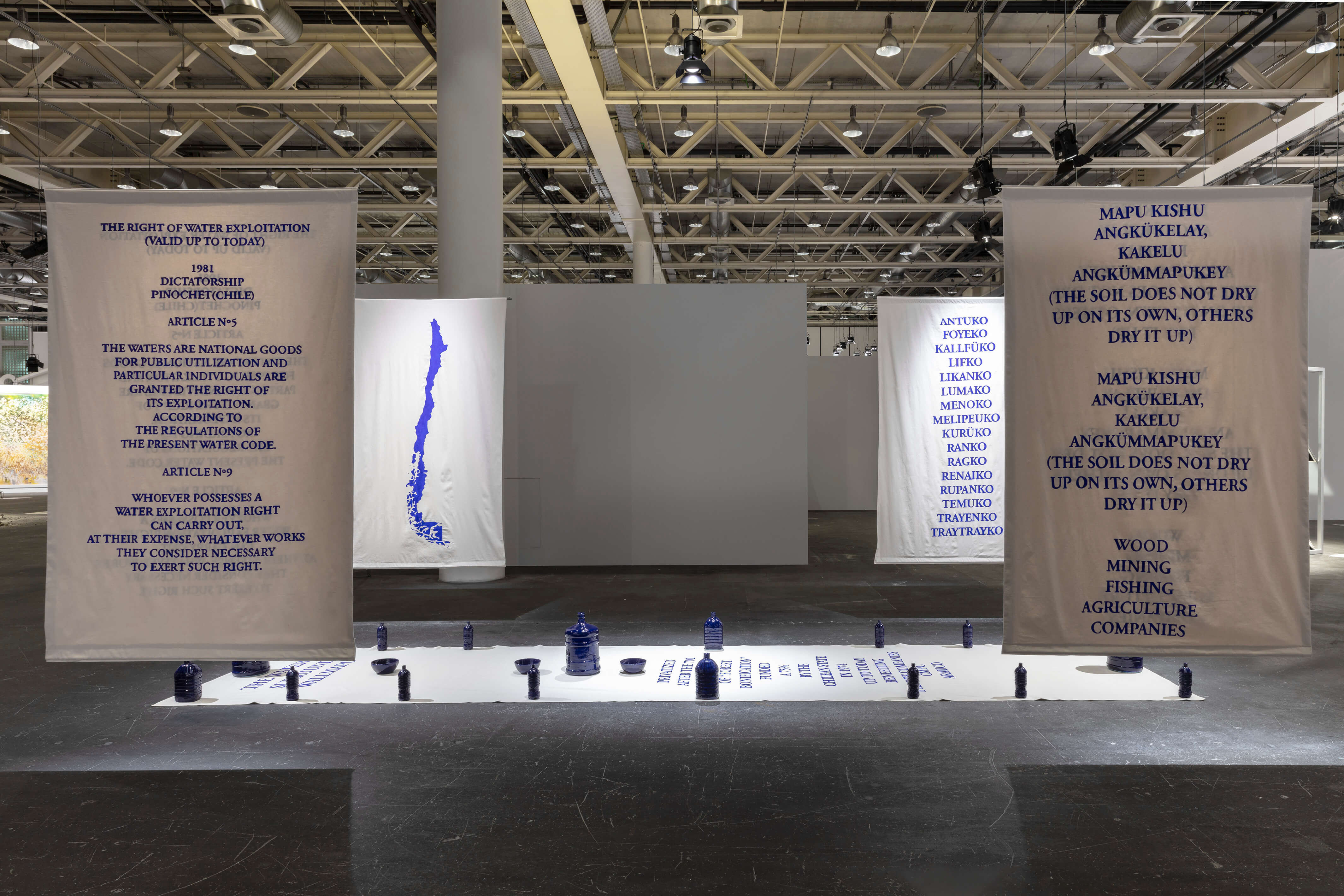

MS The artwork/performance you presented with Labor at Art Basel Unlimited, “Ko ta mapungey ka” (Water is also territory) (2020-2024), displays a poetic and political connection between water, body, territory, and the Mapuche language, tackling the historical bonds between water and the Mapuche people, amidst Chile’s neoliberal extractivism and water privatisation. Could you tell us more about this performance and explain the meaning of your ritual gestures?

SC The performance is a moment of direct connection with the spectators, a technique that proposes to expand art to other senses, including smell, touch, or sound. I first performed this work in 2020, and water is its central element. Water was privatised in the context of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship in the early 1980s, and over the years, within the deep neoliberal system we live in, access to water has become a real and constant problem. In this performance, the stage where I act is important, as it is an installation that includes the water code that legislates its privatisation; a map of Chile’s territory; place names in mapudungun, the Mapuche language; and a personal text. All these elements are drawn and painted on canvas with ultramarine blue pigment. The costume I wear – made by Lupe Abaca – is of the same fabric I paint in blue. I use my body in relation to sound; each movement emits a sound with the kaskawillas tied to my skirt. This instrument is similar to a rattle and is traditionally used in the Mapuche community to make supplications in relation to nature. I transfer it to the performance as a political claim about the waters, about their situation. This instrument has a strong connection with rivers, the sound of water and stones; traditional stories speak of its relationship with the waters. The star drawn on my face is the morning star or Venus, a planet that marks the beginning of the day and also guides part of the Mapuche worldview. In the performance, I also include herbs being burned, particularly pines and eucalyptus, two introduced tree species that, through monocultures, support the forestry industry dedicated to paper and wood. These types of crops are the main problem of the territory; they dry out the land and everything around them. Where there are monocultures, all biodiversity dies. Moreover, regarding water in Chile, the forestry industry has a significant connection with its privatisation; the owners of these extractive companies are funded by the state in a sort of subsidy for “land restitution”. It is particularly ridiculous that money is granted to those who have created the greatest water crisis in history. The performance installation also consists of a 7-metre cloth on the ground with 20 blue ceramic pieces made with moulds of plastic water containers. All these pieces are arranged to be acted upon; three of them, the largest, are carved with the words: 1981, SAQUEO (Pillage) and SEQUÍA (Drought). I hold each one up, showing it to the audience; the one that says SAQUEO contains water that is poured out during the action. Then I write a text and a drawing on the cloth, proposing a critique of the forestry law and its use of water.

MS Why did you choose the theme of water, and how do you think art in general, and more specifically this performance, can influence our new way of thinking about land, sea, and life?

SC Together with Labor Gallery, we decided to bring this performance because it made a lot of sense to act in the context of Switzerland, a country where water flows all the time as if it would never run out. Additionally, Art Basel is a perfect context to talk about power, the use of water, and other issues; the art world is not immune to these urgent conversations. I performed the piece each day for a week, and it was one of the most exhausting experiences of my life, but I think it was totally worth the effort. At the fair, I was the only artist performing their own work, which I believe gives the piece a different validity. I also think the context in which it is produced matters; coming from the global south and showcasing in such an important instance for the relationship between art and the market part of what is happening in Chile, a country that was the laboratory of neoliberalism. I believe art is a space of dispute. Although many of the places where I act or work are uncomfortable for me, as I understood contemporary art codes later in life, I think the global conversation around water, its defence, and preservation is important. Addressing, together with the spectators, how vital it is for the lives of all who inhabit this planet. For me, this is a great opportunity to present work that is made locally in a foreign reality, as its importance allows for the expansion of that discussion to other places, complicating the debates about water and its planetary reality.

MS What is the role of the feminine or queer in such an artistic practice?

SC For me, the visibility and representation of indigenous people and the LGBTQ+ community in the art world are fundamental. Historically, we have been little validated, exhibited, and represented by others; therefore, it is crucial to create our narratives and voice our perspectives. We are in a historical moment where these representations are changing, and Western art, which used to be the key to interpreting the world, is being displaced to make room for new world narratives. It is crucial, however, to work beyond identity, beyond individuality, and beyond the inclusion quota. My work has a strong link with feminism and queer theory; I believe both are spaces of liberation from the oppressions of patriarchy and colonialism because they are critical theories that provide tools. It is necessary to continue working on artistic practices that intervene in dominant imaginaries from queer or feminist perspectives, not seeing this as a theme, as it influences fundamental and determining aspects of people’s lives. For this reason, I find it important to advocate for these issues from a political standpoint, from equality, and also from peace.

Image Credits:

1. “Ko ta mapungey ka (Water is also territory)”, Seba Calfuqueo, Photo by Sebastiano Pellion di Persano, Courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City.

2. “You will never be a weye (Nunca serás un weye)”, Seba Calfuqueo, Photo by Diego Argote, Courtesy of the artist.

3. “You will never be a weye (Nunca serás un weye),” Seba Calfuqueo, Photo by Alejandra Caro Rivera, Courtesy of the artist.

4. “Ko ta mapungey ka (Water is also territory)”, Seba Calfuqueo, Photo by Sebastiano Pellion di Persano, Courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City.

5. “Ko ta mapungey ka (Water is also territory)”, Seba Calfuqueo, Photo by Sebastiano Pellion di Persano, Courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City.