Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme: On the Generative Potential of the Fragment

Basel Abbas, Ruanne Abou-Rahme

The sampling of text sound and images have become the signature of your artistic oeuvre. Fragments, ruptures, glitches and stutters. How does this language of the fragmented samples relate to the experience of being a Palestinian (or being in the world today), both conceptually and physically?

Basel: I’ll start with the experience in Palestine itself, which is a more of a literal form of something that is continuously intercepted, cut or fragmented, as a physical experience. The whole landscape is fragmented, your space is constantly being switched around and fragmented, with checkpoints and soldiers. Then there is also the idea of the loop, when you’re driving around in the West Bank, you reach a dead end, a wall that you can’t go beyond and you have to circle back. So this idea of the glitch and the fragment is a literal experience of the physical one in Palestine.

Then worldwide, we think about it more in the sense of the formal aspect of interception and how the glitch or the break itself can be something generative, it doesn’t necessarily have to hold a negative connotation but how can the break, or the glitch, or something that is meant to be an error be productive.

Ruanne: I would add that our experience of time and history is also very fragmented. History is always appearing in broken parts, for us, it’s very much about trying to retrieve or claim the fragments, because the idea of being something that’s whole is almost not possible for our lived experience. I think that’s something that’s not just particular to Palestine, but it really speaks to all kinds of experiences of dispossession and displacement, where the very living fabric is broken and ruptured. So, the question is, how do you deal with these breaks and these ruptures in a given living fabric? I think in many ways, our work has been trying to find a way, as Basel was saying, to use that fragment or that broken part as something that’s generative, rather than something that is just a negative outcome of a history of oppression and suppression.

So how can you subvert that fragmentary experience of living in parts, where there is no continuity and things are not cohesive? The expectation that, for example, at any moment a disaster could take place or at any moment something could rupture the very ground that you are standing on. I think for us, it’s, it’s always been about really trying to think about how we use these conditions that are imposed on us, how can we subvert these conditions and from that generate a resistance practice.

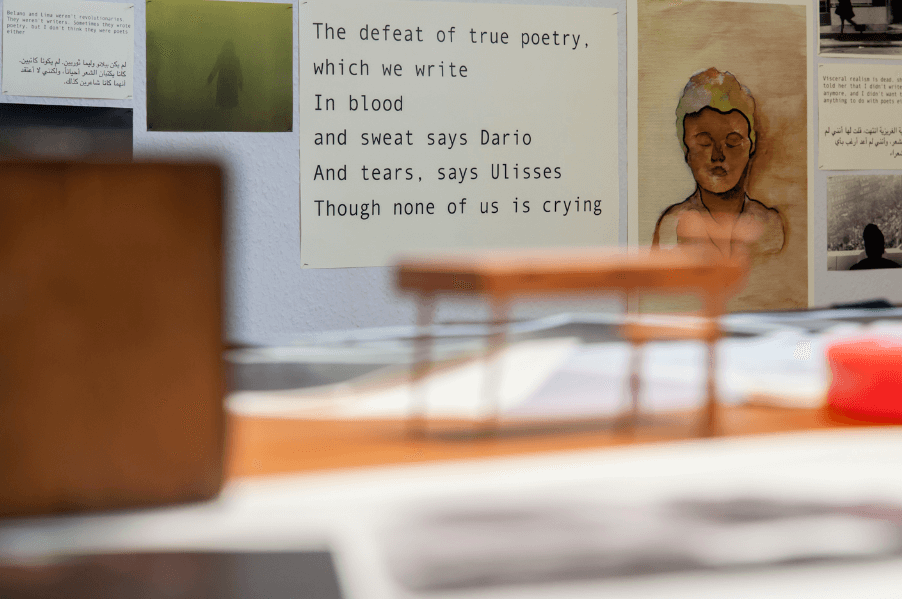

The multipart project ‘May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth’ (2020–ongoing) takes its title from the English translation of Chilean writer Roberto Bolano’s Infrarealist Manifesto (1976), could you explain this choice of title and the importance of this writer to your work – and that of literature, poetry and word in general?

Ruanne: Our relationship with Roberto Bolano actually goes back to the project we showed here in 2015, ‘The Incidental Insurgents’. He’s been a very influential writer on our whole practice, in particular, ‘The Incidental Insurgents’ drew a lot from his novel ‘The Savage Detectives’, which really thinks about the crisis that artists face in moments of political descent, but also failure, the failure of revolutionary moments and what happens to the people that continue working after those kinds of historic failures. So what happens to the figures that don’t necessarily die in a revolutionary struggle or even in prison, but the people who remain in the aftermath of a certain mode of failure or heartbreak, or even in the face of things that we thought may be possible and then appear impossible.

‘The Savage Detectives’ contains at least 40 different perspectives and positions and meanings between spaces and times. So formally, the multiplicity in the novel significantly impacted our practice.

Basel: Yes, there is a multiplicity of voices, the book itself moves grammatically between the voices of the different characters. It moves between the we and the I, and the they. That was very influential in our practice, how this is maybe about us, but also about the viewer and so it’s a way of implicating the viewer in the project. So with ‘The Incidental Insurgents’, you have two characters mostly with their backs turned, that you never really see and these characters are meant to just take up the position – anyone can take up that position – there’s a call in the work to take up that position. I think ‘The Savage Detectives’ has that component.

Text is very central to almost every project that we work on, all our works formally start with text, and this text sort of acts like a script to the whole project. Then the sound is actually built to the text before we even film, it’s not finished sound, but the conceptual ideas of the sound are made to the text and then the filming process starts. It’s not a conventional way of creating video works.

Ruanne: Poetry is a very big part of our work and what’s important for us in the in the poetic form is the way it takes apart and deconstructs language. That’s what’s very interesting for us, that process of deconstruction, of taking apart, breaking apart something and remaking it, something that’s needed for our times, because so much of what we feel is the issue, is that our ability to imagine different possibilities and different ways of being in the world are stunted because they’re saturated with the way that things are now. Poetry is personally also a big part of our lives, my grandmother was a poet, she worked a lot on publishing other Arab poets and translated Arabic poetry into the English language and into many other languages. Literature in general is a large part of our imaginary world.

Basel: Both of our mothers are translators.

Ruanne: I think that it feeds into our interest in song, because the oral poetry tradition is very strong in the Arab world. It’s a very oral culture and oral poetry has a very long history of being a critical part of testimony in the Arab world, and it comes with a lot of improvisation. The way in which forms of songs would move between spaces and times, and be narrated and re-narrated, all these inscriptions that happen across time and space in something that begins as one form of a song or a poem, but continues sometimes hundreds of years and there’s all these adaptations and mutations and improvisations. So it becomes a very important living archive testimony that I think is not always looked at enough, because it’s not necessarily always reported in a particular way. Many of these forms are transient or oral because they appear in song form or they’re spoken poetry, which has a very long tradition in our culture, so it’s a really fascinating for us to work with texts both as an image in our work and as a sonic material.

In 2015, here in Sharjah, you were awarded 2015 Sharjah Biennial Prize for ‘When the fall of the dictionary leaves all words lying in the streets (2015)’ the third and final chapter of the “Incidental Insurgents” installation (2012–15). The work explored the liminal space between the political present and its unseen potential direction, how has your work mutated and evolved since then and could you tell us a little about your performance in Al Mureijah Square this year?

Ruanne: Our work is very intimately connected to what’s happening on the ground and also people’s practices and struggles, so it’s definitely changed a lot, given the conditions – when we started. ‘The Incidental Insurgents’ it was at a moment of revolutionary upheaval across the Arab world, which we don’t see as something that failed, but rather as something that’s still incomplete, yet there have been difficult setbacks and developments since then. If we look back over the last 10 years, it’s been in many ways very catastrophic for people, so we’re really talking about nearly impossible conditions that we find ourselves in, and definitely our work is constantly responding to these conditions. If you look at our project ’May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth’, there was a real reason that we turned towards people’s practices of song and dance as a form of resistance, as a way in which people are holding onto themselves and to community and to space and laying plain to their story. I think people themselves found a lot of impossibilities in what would be more than direct kind of political actions or political articulations and in that moment, in that space. Song became a really powerful space of resistance for people and for communities.

The project really picks up on something that’s already happening and tries to amplify it, we have been thinking a lot about what it means to be in negative space and also about mourning, what it means to be in a constant state of mourning, what does it mean to be exposed to different forms of violence that are taking place consistently, all the time. From these questions we really started to think about what it means to live in negative space, also what does it mean to constantly be an unwanted people or, if you think about the crisis of refugees worldwide, that has only intensified in the last 10 years, what does it mean to be illegal, to be classified as an illegal person, what does it mean, not just in a kind of political or social sense, but more on a much deeper psychological and existential level.

Going back to the beginning of our conversation, one of the biggest things for us is how can we think about our emancipation from this condition, from the logic of the condition itself? So what happens if we embrace being in the negative? What happens if we embrace the idea of something that’s broken, rather than trying to fix or repair the break? What happens if we stay within the break? What kind of openings can emerge? And that goes back to your question about the fragment, right? We also did a project that thought about the site of the wreckage as the site of potential from which things can once again emerge.

This piece is not in contrast to ‘The Incidental Insurgents’, but you can definitely see a kind of shift, because I think it’s also become very important for us to sit with that rupture while still trying to figure out how can we not be bound by colonial capitalist imaginary, but without holding onto this notion of politics of repair, which I think doesn’t always work, there are moments when you’re not in a moment of repair, the situation in Palestine right now is not one where you can think about a politics or repair, it’s an impossible thing. So then what happens if we start to think about that differently?

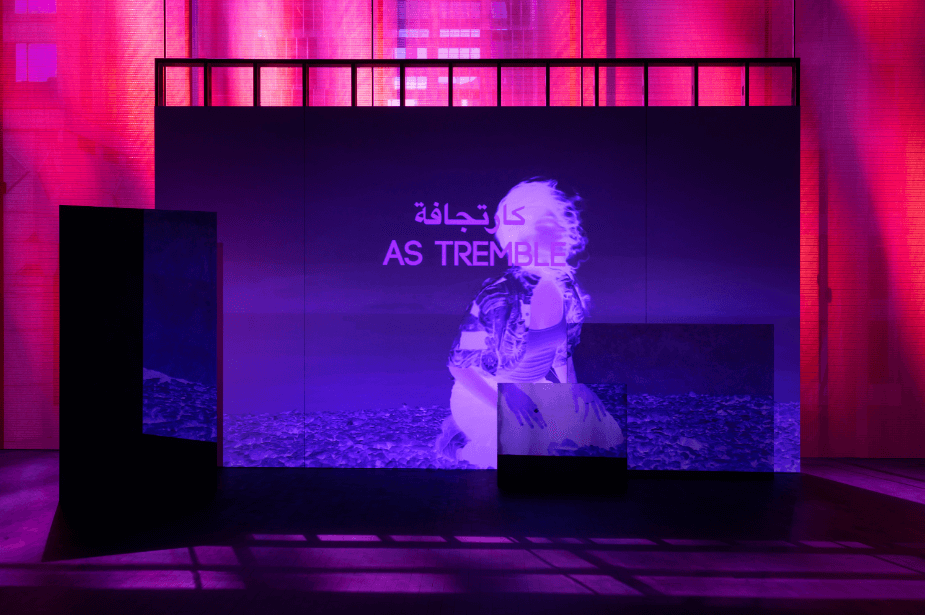

The piece that we’re presenting in Sharjah is part of ’May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth’, a project we’ve been working on for many years and it has different parts. It’s very much thinking about the relationship to land and haunting. In many ways, for Palestinians or people who have been through this position, the relationship to land is really one of love and also loss and longing. So this sense that you are haunted by the land and place itself is something that we’re thinking about a lot, and increasingly our work has been thinking about what are the stories and the inscription that the land or non-human life forms tell. What are the resistant practices that are actually embedded in this much longer, deeper time span than any one human lifetime. That has really emerged organically from our work in Palestine, by filming in specific spaces, it really has emerged from our encounter of certain kinds of vegetation that resist colonial erasure.

Basel: For this iteration of the work the land, flora and non human forms have become like characters now in this work. We’ve worked with that several times before, but I feel this time it’s more pronounced and taken centre.

Ruane: We’ve thought a lot about sonic inscriptions because we’re doing a lot of research on songs that travel between times and spaces. That very much mirrors this feeling that every time it’s performed again, it is that person’s song, but it’s not just theirs, it’s part of this common registry almost, but it also speaks to the way in which within the actual song itself, within the words and the rhythm and the melody are all these different inscriptions and histories where, the story is yours and yet it’s not just yours. So how do we think about something that’s collective or common or we without trying to create something that’s homogenous – I think any kind of collectivity that we need to think about now needs to allow for multiplicity and tension and things that don’t quite sit right with each other.

When we were filming part of ’May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth’ in Palestine, we would go to these outdoor sites to film with the performers and we had this experience where there was a specific melody that that more than one performer took, every time they would perform outdoors, there were certain birds that would come and start singing with that refrain – that was a very powerful moment for us – it made us think about how actually that refrain is already there, it’s in the land, in the space, it’s been there much longer than us that in that moment. So what are the inscriptions that we don’t even see that are being held by these non-human forces in this space and in that is an amazing resistant history, that’s still resisting. So we have had these very powerful encounters that made the land itself a big part of the work. With our work things always come into it, it’s not like we go knowing exactly it is we want – through the process of making the work, things become clear to us. We have had more than one really powerful experience like that, but we’re not very spiritual people or anything like that!

Basel: This part of the project works a lot with the site as well. It’s a very site specific work in an abandoned outdoor space with a courtyard and no roof, where trees and plants still grow inside. It’s completely run down and so it was perfect for what we were thinking about and we’ve told them not to touch anything. We have just left it as it is, and just cleaned it up a little bit, it’s a non-conventional space, it’s been a nightmare editing for it, but other than I’m excited and it’s very different to how we usually work spatially – we always work very site specifically, but this is really, you know, it’s exciting to be able to get out of a white cube space or a gallery.

You divide your time between New York and Ramallah, do you have studios in both locations and could you tell me a little about your creative process as a pair, who does what?

Basel: We do spend our time almost half the year in New York and other half in Ramallah. We had a studio in Ramallah until the pandemic hit, and now we have a rented space when we go there. We got stuck in New York, so when we go back there we rent a space and we have storage that is full of equipment, most of our production equipment is in Ramallah – all the lenses, cameras, microphones. Then in New York, we do a lot of the post production, so a lot of the music equipment and synthesisers and drum machines, and the big computers for the editing and the printers, those are in New York. It’s not exactly clear cut, but more or less I would say that the majority of the production happens in Palestine, and the majority of the post production happens in New York. We basically do everything ourselves -we film ourselves, we record our own sound, and we then do all the post-production ourselves to the point of mixing the sound and mastering it and the colour correction – it’s all hands on and that’s a very important element that we have.

When we first started working together, I came from a more of a sound and music background, and Ruane came more from an image and text based background and we spent a long time exchanging the knowledge we both had. So Ruane taught me how to film and how to edit and I taught her how to use the synthesisers and the sound editing software etc – we were really trying to make it a true collaboration, also formally, so we worked hard on that, and I think there’s a flow now. Sure, Ruane is a much better video editor than I am and so she does do most of the hands on editing, but we’re sitting in the same studio, we’re constantly working together on things formally and conceptually. We create reading lists for a specific project and we read the same things and we discuss them a lot. So I would say 70% of the practice is talking, there is a lot of talk!

Ruanne: We try as much as possible to not have a ‘you do this, and I do that’ kind of approach but of course Basel is technically stronger in sound, and I’m technically stronger in image based work, but we are working in the studio together the whole time and very often when we’re working on our video and sound pieces new things emerge through a live performance setup. So actually many times before we are editing, we will be using live sound and video software to jam together. Specifically with the ‘May Amnesia’ project, with the first part of it that we showed, we really wanted to push that sense of watching a live performance, because a lot of our oral and aesthetic forms come from live performance situation where we’re experimenting and we’re jamming together. The way that you trigger live sound and video in a performance context, your body is much more indicated than when we’re just editing in a linear way. We have record hours of ourselves jamming throughout live recording, we’ve started to also do a lot of vocal recordings for a lot of our projects – it’s a very fluid, setup between us and the studio.

The only thing that’s not fragmented then, it seems!

(Laughs) Basically!

We have covered this already but to reiterate, sound is a very important element to your practice, could you tell us about its resonance in relation to the image, what can sound do that the image can’t?

Ruanne: I mean, there’s so many things sound can do that the image can’t – the most important thing is that the way that sound cannot be contained, I think it’s malleability, the way it permeates and penetrates and structures, is very interesting for us. Sound is a much more porous material and it can be very subversive. We really enjoy the way that sound has something that’s far less tangible than the image. The image always has something that gets fixed and sound is always unfixing and misplacing, its a really important part of our practice.