Delaying the Arrival of Meaning – A conversation with Romeo Castellucci

Romeo Castellucci

Ten years after their last meeting during Art Basel, Romeo Castellucci returns to dialogue with Mara Sartore on the occasion of the world premiere of “I mangiatori di patate” (“The Potato Eaters”), presented at the 2025 Biennale Teatro. A work that embodies his ongoing quest for a theatre that escapes traditional forms – a theatre suspended between ritual and reality, enigma and corporeality.

MS – Ten years ago, in Basel, we spoke about “Le Metope del Partenone” (The Metopes of the Parthenon). I remember it was a very intense conversation; the show itself was incredibly dense. After seeing “I mangiatori di patate”, I reread that interview. It’s really been a long time, ten years… One expression you used back then stuck with me: “magnificent inertia”. You were referring to a life not so much chosen as respectfully endured. Ten years later, do you still feel like you’re being “carried along like a log in a river”? Or has something changed in your relationship with the artistic gesture?

RC – I can’t say, being at the short-sighted point of the question, which is the centre of the question itself. I was born in a certain era, in a certain place, climate, language, and within specific cultural and religious coordinates – and that’s how it is, rightly so. “Chrono, Clima, Lingua”. I could never be, say, a Buddhist – not because I don’t think the Buddha is beautiful, but because that’s not the river I fell into. Choices are made on other levels, but not about these macro existential conditions. Of course, I’m speaking for myself.

MS – So, over these ten years, have you not experienced change or transformation?

RC – No. I don’t know. Yes, maybe.

MS – “I mangiatori di patate” is a work conceived specifically for the island of Lazzaretto Vecchio.

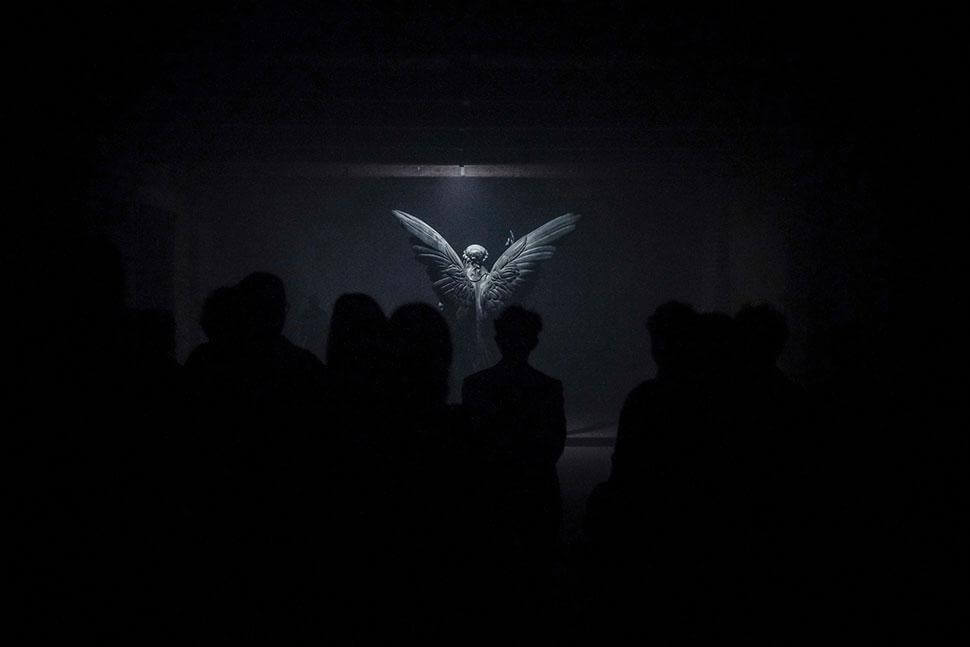

RC – That place wasn’t something I conceived or desired, but rather something I found. That place – every place – is a character full of spirits. In the courtyards of the island of Lazzaretto, there are still thousands of bodies buried in mass graves. It’s a site marked by segregation, illness, abandonment. I don’t believe it was ever a place of healing, but it’s undoubtedly a place of memory – a memory that is both blurred and precise. Those long corridors, the perspectives leading into darkness, shaped the wandering condition of the spectator.

MS – It was an intense experience, as your works always are. I was also intrigued by the title: “I mangiatori di patate”. Everyone references Van Gogh’s painting. Was that intentional, or is it more distanced?

RC – There is a reference, even though I didn’t want the audience to immediately think, “Ah, it’s Van Gogh.” That’s not the point. But of course, there are some resonances. Van Gogh the man moves me deeply. His Tragedy. That particular painting deals with poverty, hunger, dignity. It’s one of his first oil paintings, very far from the colours that would come in the later phase of his work. He painted “The Potato Eaters” when he still wanted to be a preacher, and lived poorly among the poor in the Borinage – the most miserable region of Belgium, inhabited by coal miners and destitute peasants, people he loved and respected.

MS – In your brief description of the performance, you mention some keywords: fall, statue, hunger, caricature, history, three. This “three” is curious. Where does it come from? Is it a Trinity? What is “three”?

RC – No, I don’t believe it’s about the Trinity.

MS – It’s unusual to place a number among such words…

RC – True. But each of those words hides, in turn, a constellation that reveals itself in every spectator, who, if they choose, draws their own lines, composes their own drawing, something that is just their own, private. It’s not up to me to say what that sequence means. My work is about delaying the arrival of meaning. If, as a spectator, I understand what a work is trying to tell me – or I understand the artist’s intentions – then I feel disappointed, I grieve. Art is not information, nor is it the domain of good feelings or the “right thing,” which is always condescending and consolatory.

MS – Perhaps the enigma is the central element of your work. We spoke about this ten years ago as well…

RC – “Enigma” is a formidable word: we know it holds a solution, but it keeps it hidden. Every true enigma contains a sting. The art I respect is enigmatic. It slows down meaning, without denying it.

MS – In “I mangiatori di patate” I recognised three fundamental elements: body, sound, light – or rather, light and shadow. I perceived these as the pillars of the performance. The wrapped body, the corpse, the living body, but also the aesthetic body – this woman figure, so white, dead, yet statuesque, beautiful. Sound, as a dramatic and perceptual element. And light, in contrast to darkness. Would you add anything else, or are those the main structural elements of your scenic enigma?

RC – You described it well: those were the three fundamentals. The light came directly from outside: it was daylight. Black curtains opened, and the rays of the sun – “him”, in person – entered and visited total darkness. The human body was initially tossed into black garbage bags. Then, after a certain path, one of these opened and revealed a bloodless body. The woman’s white skin indicated an absence of blood. The theatrical makeup revealed the corpse. In particular, in the mouth of this pale body, a “beak” was implanted – a black device that moved autonomously, similar to the lip plates used by the Dinka people of Sudan. The object fit like a bit into the dental arch. The “beak”, by moving, brought the body back to life through language. Here, language was an implant, an original violence, an occupying force. To produce the sound, Scott Gibbons used the voice of a young man suffering from schizophrenia and recorded his auditory hallucinations. We used those recordings. They were abrasive voices that assaulted the victim’s body – voices of command, but only the tone of command, because meaning was absent.

MS – There was also collaboration on the dramaturgy with Piersandra Di Matteo. How did you work together?

RC – It’s an important job that happens during the preparatory phase and, later, during rehearsals. Piersandra’s role – besides philological precision – is to be the devil’s advocate. That’s what a dramaturg should be: a “diabolical” presence that divides and causes crisis, that shows you failure as a possible horizon.

MS – Were there any major challenges? Dramatic moments?

RC – How could there not be? The working conditions in Venice, in that location, were tough, and we had less than four days of rehearsals. I wanted it that way. My work is mainly mental. I don’t develop ideas during rehearsals. The more time I spend rehearsing, the more confused I become and lose clarity. First come the ideas, then comes the friction of dramaturgy, which makes them possible on the plane of reality. All of this has to happen in a short amount of time.

MS – While I was among the audience, I wondered whether our presence was truly essential. In “Le Metope del Partenone”, for example, the spectator was essential, almost part of the scene. Here, I felt more like a museum visitor.

RC – That’s accurate. The structure was classical due to the nature of the space. There was a path that predisposed the viewer, and during the journey, after a long corridor, one arrived at a cul-de-sac, where a dark force blocked the way forward. The audience was forced into a frontal view, that of Classical Representation.

MS – Ten years ago, we also spoke about another issue. We were at Art Basel, so in a context closer to contemporary art than theater. One of the distinctions we discussed was between the experienced time of performance and the narrated time of theater. But neither in “Le Metope del Partenone” nor in “I mangiatori di patate” is there narration. There are enigmas, symbols, hints… So this tension between theater and performance returns. Back then you rejected the label of “performance”, saying it was something else. And yet, as a spectator, I felt very directly involved – also because of the strong artistic, aesthetic figures you presented. In your works there is always a strong aesthetic, but here it seemed even more refined.

RC – Yes, I understand what you mean. But the divide between theater and performance remains sharp. On a stage, the ontology of the here-and-now which defines performance doesn’t apply. Theater deals in falseness, and fiction is its liturgy. The essence of theater challenges and contests the verb to be at its root. It doesn’t seek truth because it fights for liberation from it.

MS – Of course, though nowadays many visual artists work with performers, creating pieces that seem to draw from theatrical language…

RC – Yes, of course. It’s understandable. Theater is powerful because it’s a “force of the past” pregnant with the future. Theater was born hand in hand with religion, in the enclosure of a Neolithic cave. The Art of Behaviour, as we know it, is very recent – generally from the ’60s–’70s, in a time of urgent political intensity. Back then, exposing the body was a dangerous gesture. Nudity was politically charged, and you could get into serious trouble for it. Today, the naked body is a demand of cosmetic advertising.

MS – Our visual imagination has changed in these ten years. Theater has changed. How do you position yourself in all this today?

RC – Look, I don’t know. I’m not smart enough to distinguish things. And I certainly don’t know how to situate my work. I don’t worry about naming it.

MS – Yes, I figured that wouldn’t be your concern per se. But still, there are colleagues, references, a cultural context you belong to. Is there a theatrical or artistic environment you feel in dialogue with?

RC – Yes, inevitably. But if you ask me whether I feel part of the theater world, I’d say no. Not out of snobbery, because I don’t think I’m better than others. But I must admit I don’t enjoy going to the theater. One of the few directors I truly admire is Christoph Marthaler, the greatest living director. I’m also very drawn to some plastic artists – a couple dozen at most – even though visual art is often painfully obvious. Then there’s choreography, a refined discipline, especially when it’s free of messages and athletic bodies – I find those repugnant on stage. I listen to classical music when I need to cry. I read fiction and little poetry. But the language that moves me most is cinema. Though even there, the disappointments are many, total, devastating… But yes, cinema is what seduces me.

MS – There’s also a dreamlike quality to your world. Are you someone who dreams? Do you have night visions you later elaborate?

RC – No, I’m terrified of dreams. I don’t like dreaming at all, nor trying to remember them. When I unfortunately do remember one, there’s always something awful and frightening. I purposely forget them. I prefer not to open that door.

MS – Finally, after this world premiere of “I mangiatori di patate”, what’s next? Are you working on something new? Will this piece travel, like “Le Metope del Partenone”?

RC – Yes, but probably with a different title and form. I’d like to retain certain elements – like the language-hole. The rest will change. I’d love to make a Comedy – the highest and most difficult form of Greek art, in my opinion. But I don’t think I’m up to it.