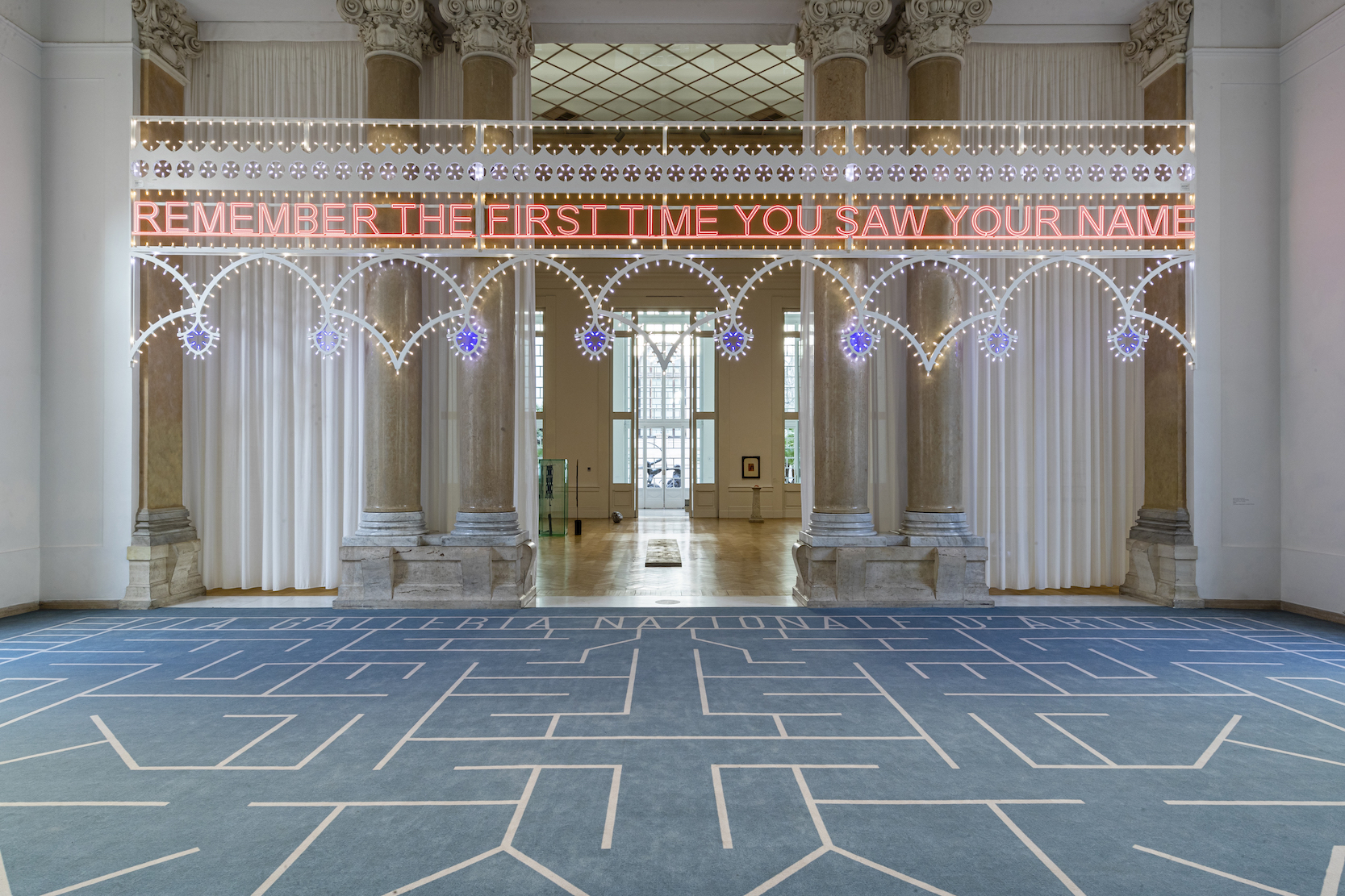

“I say I” at La Galleria Nazionale, Rome: an interview with the curators

An interview with curators Lara Conte, Paola Ugolini and Cecilia Canziani.

Lara Conte, Paola Ugolini

I’d like to start from the origins, how did the exhibition come about?…

Lara Conte: We were contacted by Cristiana Collu, the director of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome, the idea was to create a curatorial team with different lines of research and study in order to put together an exhibition on the relationship between artistic creativity and the broader dimension of feminisms, of the theories of feminist thought in Italian artistic research. Our investigation began by reflecting upon the legacy of Carla Lonzi, in relation to the archive that was donated to the Galleria Nazionale in 2018. The methodology was go into depth, but also to have a look at different perspectives, the title in fact “Io dico Io” settles a series of thoughts that were stimulated by Carla Lonzi, but which go onto trace a much broader and transversal discourse. The idea was not to work on a limited generational dimension, but to broaden the discourse on the art of women in Italy, creating as a polyphonic and trans-generational dimension of the artists involved, so much so that we have more than 50 artists , from Antonietta Raphael Mafai to Benni Bosetto.

The idea was to identify several themes: “I say I” arises from the urge to speak, to speak in the first person and therefore to start from self-representation – as an affirmation of the self, therefore a way of telling oneself and tell stories from a situated perspective, defining new points of view on the world. From there we identified other themes: writing as a story of the self, the idea of the body, which has been a very present theme in women’s art since the 1970s: we investigated this by choosing the different ways of looking at the body: the body in terms of size, the body repositioning itself after a trauma, the idea of the fragment; we then worked on other themes such as self-portrait and self-portrayal in relation to the poetics and politics of the gaze, in relation to preciousness as a resistance to homologation and to the stereotypes of a legitimate gaze and a dominant patriarchal perspective …

How did you find working in a group?

Paola Ugolini: Cristiana Collu called all three of us to work together and I must say that it was a brilliant idea, a gift; I love teamwork, I believe in the collective, I believe in shared practices; with Cecilia and Lara a sense of harmony was immediately struck; despite being different people we worked together in sync, each bringing their own skills, without ever overlapping or crushing each other. It is a shame that the exhibition is over, because we really enjoyed working together!

When Cristiana Collu summoned us to imagine a narrative to honour the legacy of the Carla Lonzi archives by her son Battista Lena – this is an important donation because many documents, even unpublished, can also be studied on the online platform of the Galleria Nazionale (we owe it to the sponsors and partners who supported us such as Dior and Google Art & Culture which digitalised not only the Lonziani materials but also the works of female artists who are part of the museum’s permanent collection). It must be said that even for those who cannot travel, the site now allows you to navigate through the works of the collection with great ease. We then invited several colleagues and friends, journalists and art historians to participate in a small series of podcasts dedicated to the story of the works of female artists in the permanent collection. So the polyphonic story overflows from the exhibition and insinuates itself into the apparatuses of this institution. The task did not seem easy to us at the beginning; in 1969 Carla Lonzi publishes “Self-portrait”, a fundamental and seminal essay for the rewriting of the practices of both relationships with artists and the story of art – a fundamental piece of what Carla Lonzi calls “il racconto dell’autenticità” (“the story of authenticity”) – but in 1970, after the foundation of the Movimento di Rivolta Femminile (Women’s Revolt Movement) with Carla Accardi and Elvira Banotti, Lonzi decided to abandon her work as an art critic to devote herself completely to militancy; in 1976 there was a spit with Accardi and with most of the artists who were part of the women’s revolt movement. In reality, our work was about mending and repositioning the role of Carla Lonzi as an art critic and of the often cumbersome relationship in Italy between feminist militancy and the figurative arts. As Lara said, in order to be able to realise this great trans-generational and polyphonic narrative, we made use of the readings not only by Carla Lonzi but also of other philosophers such as Silvia Federici, Adriana Caravero, Annarosa Buttarelli, who also collaborated in the curation of the archives on display and we identified some trajectories with which to start.

Earlier, with your first question, you used the word “origin”. Here the matrilinearity and the origin are one of the trajectories down which we traveled, beginning with the germinative and seminal work “Origine” by Carla Accardi, created in 1976 when she separated from Carla Lonzi and with Susan Santoro and other artists in the cooperative of “Beato Angelico”. In her first solo show at the Cooperative, the artist presented work that was aesthetically disconnected from her usual practice, a self-narration of her origins from a matrilineal point of view, an intimate work of reconstruction of her genealogy, alternating black and white photographs found in the family album with strips of transparent sicofoil, an innovative plastic material with which in 1966 she made the famous “Tenda” (curtain) which for us is one of the most representative works of “feminist art”.

So “Origine” was one of the departures, there were other common threads that guided us within this exhibition: writing, self-representation, the gaze, the body also understood as erotic and desiring, so much so that we have exhibited three watercolours by Carol Rama, and “Mount of Venus and Beyond” by Susan Santoro.

What was the value of Carla Lonzi’s work and how did she influence and participate in the artistic movements of the 1970s?

Lara Conte: We did not start from Carla Lonzi to analyse the complex relationship between art and feminism in Italy on a historiographical level, we instead started from the present to confront ourselves with the legacy of Carla Lonzi’s thought, through her writings, her diary writing. , crossing her work to define our perspective of investigation on feminist art in artistic practice and on a theoretical level. This therefore excluded a vision only aimed at activist and feminist militancy, but opened to other questions, such as the aesthetics of the domestic, which includes a political vision, a feminism which stems from difference, from the existential dimension, an aesthetic of everyday which traces a militant vision. And then physically on display we dedicated a room to the Carla Lonzi archive, curated by Claudia Palma and Annarosa Buttarelli.

Our investigation of the Lonziano archive begins with a vision of the archive as a practice, that is, it is based not only on a documentary approach of study: we have commissioned works by artists inspired by the archival documents and the themes connected to them, therefore inheritance and genealogies. With this approach, the document, therefore, is no longer just an object of philological reconstruction, but a creative cue to deeply reactivate the idea of inheritance. Inspired by a visit with us to the archive, three artists: Chiara Camoni, Alessandra Spranzi and Maria Morganti have worked on ideas that open up issues that summon up in the present and in a theoretical and practical perspective, what it means to deal with such a thought crucial for Italian feminism, going to the essence, to the meaning of authenticity (key term of “Autoritratto” Self-portrait).

Practices of self-awareness, that today can define new ways of re-reading the history of art. This also crosses the studies carried out by our other colleagues such as Carla Subrizi who recently published “La storia dell’arte dopo l’autocoscienza. A partire dal diario di Carla Lonzi”

(“The history of art after self-awareness. Beginning with Carla Lonzi’s diary ”). We worked in this direction to question ideas on difference, collective practice and dialogue which lends itself to a political dimension, something which found by curating this exhibition together.

What was the selection process for the artists? I guess it wasn’t easy, did you manage to involve all the artists you wanted?

Paola Ugolini: When you imagine an exhibition you always dream big, with the ideal of an exhibition that you would like to achieve, but then you clash with the budget, with the fact that some works are already on loan at other exhibitions … We we would have liked two works in particular: Carla Accardi’s “Tenda” from 1966, a work that the artist had imagined with Carla Lonzi, a happy idea of a mobile home, transparent, open and light, a house that is not a burden, but which becomes the home of a nomadic person, free, not forced into a closed domestic space. We were very sorry not to be able to have it but the work was on display for the retrospective dedicated to Carla Accardi at the Museo Novecento in Milan. Covid has postponed the exhibitions and consequently the loans.

We also had to give up two works by Chiara Fumai, a friend whose loss left a great void in the world of contemporary art, a young artist who left too soon and who brought female figures back to life such as Valerie Solanas, a great feminist theorist who had the condemnation of memory for writing things that in 1968 were impossible to digest. The two works have passed from the museè pour l’Art Contemporaine in Geneva to the Centro Pecci in Prato and now we can’t wait to go and see them on display in Prato.

Returning to the selection process, we approached it in reverse. First we imagined some guidelines that we wanted to follow conceptually, then each of us put forward names and works that we believe were adherent to that discourse, starting with historical artists such as Carol Rama, Carla Accardi, Marisa Merz, Irma Blank, Giosetta Fioroni, Ketty La Rocca and then we expanded because we wanted to bring it up to today and perhaps even the future. We mentioned Benni Bosetto before; she created a work on commission, by filling an 11-metre long wall with graphite and pencil drawings and imagined – referring to the philosopher Rosy Braidotti – a post-anthropocentric world of mutant, nomadic and asexual bodies that also hybridize with the animal and vegetable world. We started from the roots of feminist thought and we saw that we could create eccentric branches leading into many different territories.

How has the role of women in art changed from the 1960s to today? And how will it change? How do you see it evolving in the future?

Lara Conte: Io dico io is in the present, as an awareness by which to look at the past and the future. It offers itself as a space of relations, of shared time, of gestures to be made together, in order to make the present resonate: “adesso so chi sono, posso essere coscientemente me stessa” (C. Lonzi). (“now I know who I am, I can consciously be myself”)

We wanted to work on themes and issues that we consider still open and that from a historical perspective reverberate with incisiveness in the present. For example, the idea of a creativity that can redefine spaces – from the domestic to the relationship with nature – is a theme that runs through the history of art and feminism. But we also think of the dimension of self-representation, of the body and sexuality, of writing as a story of the self, or of the relationship between architecture, power, gender and body.

To give an example, self-representation and gaze are connected to the emergence of a “nomadic subject” (R. Braidotti) who questions roles beyond the binary frame of man and woman. We have traced a trajectory that goes from the photographs of Transvestites by Lisetta Carmi to the intervention of Benni Bosetto, where her site-specific mural Forss also explores the hybridization of human beings with the animal and plant world in a new post-anthropocentric vision.

Reconnecting myself to Benni Bossetto and the concept of canceling the distinctions between the sexes in which the new generations identify themselves, I wonder how much it is important for women and artists today to be self-aware, how important it is to remember and treasure women’s political struggle which still remains relevant today.

Paola Ugolini: This is a political question so I will try to answer politically speaking. Surely today there is a great polarization between young people, many males and females have a fluid relationship with their being and are not too entangled in the patterns of masculinity and femininity, which are however deleterious because they are social constraints. I am not afraid of a cancellation of the sexes, but I hope that the awareness of our differences and similarities can lead us to a collaboration between the sexes, to mutuality. There shouldn’t be one sex predominating over the other. When we talk about patriarchy we are talking about a prehistoric period that began in 3,500 BC. and that still exists. From the studies, from the archaeological excavations through which we reconstruct the social modalities of a people, we deduce that before this date there were these mutual societies where the two sexes cooperated harmoniously for the collective well-being.

When I see my daughters approach homosexuality, transsexuality or non-binarity with absolute ease, well, they have a relaxed, non-judgmental and highly accepting attitude. They wish for a world where everyone can be free to express themselves as they feel best, without harming either others or themselves for having to remain imprisoned in a pre-established order that is very often violent.

Femininity is not necessarily only of women, the feminine must be understood as a vision and reading of the world

Paola Ugolini: The feminine as well as the masculine will always exist, the important thing is that they are not polarised

Lara Conte: In our exhibition we have also dealt a lot with the theme of difference, of claiming a feminine and feminist perspective that is also the possibility, through being a woman, to recognise

e one’s own identity. What does it mean to be a woman within a discourse that takes on different nuances, to make the idea of difference resonate.

Do you think a feminism exists in art today? Do you perceive it in the younger artists?

We didn’t work with very young artists, because the idea of a museum like this didn’t push us to the recent generations, it was a deliberate choice.

As we have said, for us feminist perspectives resonate in many ways of making art today: from the activist and militant dimension to the many issues that we have already identified.

Alongside the exhibition we have also activated a series of talks, curated by Anna Gorchakovskaya and Francesca Palmieri, where the gaze has become even more transversal and transgenerational. Sociologists, philosophers, historians… have shared their thoughts on certain issues that affect women today in relation to the themes of the exhibition. It was a way of welcoming requests and perspectives that met our point of view and constantly kept it enriched: the idea behind Io dico io / I say I was in fact to create an open device that could generate a dimension of debate and dialogue in constant evolution.