Vetrina #13 – Night Eyes: Mariana Hahn in Conversation with Mara Sartore

In this conversation, Mariana Hahn reflects on her practice rooted in the body, memory, and material metamorphosis, her use of copper and salt as carriers of time and narrative, and the layered emotional and historical resonance of creating work in Venice.

Mariana Hahn

Mara Sartore – Your work spans multiple mediums and geographies, often revolving around the body, memory, and material transformation — what originally drew you to these themes, and how have they evolved over the years in your practice?

Mariana Hahn – As it often is, our personal history is the thing that draws us to look at specific things. As you maybe know, I started with painting as a student in London. At the time, though, it felt like it was not enough for me—I mean physically. I had this urge, and I didn’t know what it was until I saw the exhibition Danser sa vie at the Pompidou, curated by Christine Macel and Emma Lavigne. There, for the first time, I saw the works of Pina Bausch. Her work pierced me—literally. I then bought the DVD of Café Müller, and once I was back at home, I watched it four or five times in a row. I cried; the effect it had on me was tremendous. It hit me so hard. It showed the potential of the body. Café Müller is like a scalpel, going with precision into layers of our physio-pathologies. Working with the body is a great way to confront our wounds —the body keeps the score.

So back then, as a young student, I had no idea about dance or performance. I was so young and ignorant still. But it awoke something, opened a door, and from then on I had to work on performances, work with my body and its memory.

At the start, my work was really personal—it was my own Weltschmerz that I worked with. I did not yet know how to tell a more nuanced story; all I knew was that I had these fragments in myself that wanted to be used. I think those early works were way more challenging physically, and they had an element of pain—this pain I felt inside and that, for some reason, had to be expressed through my body.

The first work that was more complex and transversal in its narrative and story telling was when I looked at trauma in Torso no Torso in 2013/2014, a work I showed in Moscow at the Biennale for Young Art in 2014. I looked at how trauma might be handed on from one generation to another—specifically, the trauma of the violence that women experience during wartime. And yes, it had to do with my own history, but I did not use my own story directly. I used that of The Women of Troy by Euripides, and then the story of post-WW2 Polish refugees. I even went so far as to look at cities as beings that have trauma inflicted on them—specifically, a city in Poland where I stayed and did research at the time for six months, and then created a video performance with local amateur actors. It became a shared story, where all women became the women of Troy, no matter what period they live in.

I would see the body—its skin—as a sort of parchment, inscribed with memory, with words, that goes through so many changes linked to the experience of our soul, body and soul are one and the same thing.

This would then transfer onto other materials—like copper, or salt, or hair—and I would look at these materials, how they behave as they touch each other. Because no change happens if there isn’t a small amount of corruption. Corruption is often seen as a material becoming impure, but without it, nothing happens. It just means that one substance has touched another; it changes… and it is being activated.

Think of the alchemical blue—something beautiful I read about in a book by the Jungian psychologist James Hillman at one point: “Blue saves white from innocence.”

So I guess this is something I have always been drawn to—looking at growing, learning and specific mechanisms of how deeply rooted knowledge can be transmitted from one to the other.

I worked in many countries, and I have from the start been drawn to the stories of women, whether it be a sisterhood in China or the Kurdish women’s liberation movement, which I worked with for years. It taught me to love women—the greatest lesson I could have asked to learn—and of course, our relationship to nature, which I have been working with from the start. I have always looked at and experienced the world as something wholly alive and communicative, that has stored knowledge, that wants to be transmitted. And I am not saying this as a bystander—I myself experience it like this: for one, I grew up in a forest, which was a really great teacher. Yet, by ways that I was created, das Feinstoffliche (subtle body (in a metaphysical sense)) communicates with me, and then it finds expression in the material world, I have learnt at a very early age that whatever ever we make with our hands is an expression of our soul.

It sits in my bones. There is a lineage of women in my family who also have had this communication, so called visionnaires, wise women. Some of whom suffered greatly from the lack of a proper support system, in a society, where such ways of experiencing the world were and still are seen as apart, and are rather placed into contexts of mental pathologies.

And since a couple of years ago, I have come back to painting—and mon dieu—little did I know of the power of this medium. When I was younger, I was not ready for this yet, because through painting I find the most intimate and direct pathway from my deepest depth right onto paper, canvas, etc. I was not ready to hold that when I was younger. I needed to do a lot of preparation beforehand, for all these years, to be able to dare to do this. Also, painting is a strange thing. A painting is not really an object, and one can’t really own it, because it is something totally imaginary. So what we see—we don’t really see. I mean, what we see is not real. I’m diverging now!

MS – Copper and salt are recurring elements in your work, acting almost like carriers of memory and change — can you elaborate on how you approach these materials and what they uniquely allow you to express in “Night Eyes”?

MH – Copper, for me, is like a substratum of body. And copper, like a body, has memory. That said, all materials carry memory— carry knowledge — and are ready to share it. Copper is malleable and strong; it goes through all those changes. At the start, so clean and shiny, and then it gets patina. Yet, this is also when it becomes interesting—the patina is story. And we learn to deal with the stories by telling them.

Copper is able to navigate that thin line of when something falls apart, and something else comes to life. I can observe it with this material. It teaches me about this. Also, it is a very magical material and has healing powers — on a physical level and also on a spiritual level. Copper is so warm and communicative.

Now salt—you know, I was born in a salt city. Besides that, it’s so aggressive—gosh, it really is relentless—and at the same time so open. It carries story. It conserves, it destroys, and it creates. It really lives on the edge of Eros and Thanatos. I would go so far as to say that it is Eros and Thanatos at the same time. It’s a very complex material that evades control. It’s this rebel. And when it devours something, it shares this through different channels. Either it carries it into the air via the water in it, and we breathe it in. It is constantly changing.

Stendhal once left a tree branch inside a Celtic salt mine in Austria, and when he came back, the branch was covered with salt crystals. He said that this was love. Now this is really moving. Firstly, this branch would be so painfully beautiful, covered with those crystals—yet so fragile, those crystals. And also a bit unsettling, this embrace of salt around the branch. In high doses salt is deadly, yet in small doses delicious, and it brings out the taste of other things. Yet without salt we can’t live.

You see, salt acts as the fixed, imperishable nucleus (solidus)—regarded as the hidden mechanism underpinning the ontological leaps or mutations of visible evolution. It is the juncture of opposites. It’s a wild substance. It wants to evade definition. It’s soft and beautiful, silent and dangerous, and sensual. It is what brings change, and therefore it is transgressive. But—but—it’s so complex to work with and to understand. It basically asks you to submit.

So how do they work in “Night Eyes”? You know, I feel Venice is a city like salt and like copper. It’s at the conjunction of different things. It’s quite provocative in this sense—it opens up a lot of doors. Venice has this softness, and yet also quite a level of violence. And I mean underneath the beauty—inside the materials, the elements, its history, its body, basically—and it allowed for all these elements to interact. And this is what makes this city so very seductive. From its earliest days, Venice used salt not only as a vital preservative but also as a form of currency and a key strategic trade asset. By the 13th century, the Republic had secured a powerful monopoly over salt production and distribution, managing extensive saltworks throughout the Adriatic—most notably in Cervia, Chioggia, and reaching as far as Crete and Cyprus. This dominance was regulated and enforced by the Magistrato al Sal, the official body responsible for overseeing every aspect of the salt trade. And I read somewhere that the term fondamenta, referring to the walkways along canals, originates from fondamentum salinarum, indicating areas once dedicated to salt production.

MS – The piece featuring your own sweat imprint on copper is both intimate and socially charged — how do you balance personal physical experience with broader societal commentary, particularly in the context of vulnerability and visibility in public spaces?

MH – There are so many stories I could tell about this, and you know, when you make yourself vulnerable, people around you show their true faces. It can make them act in very powerful ways—in ways that can be perceived as negative and positive. It can open up layers of their own wounds: some cry, some laugh, some fall silent, some get so revolted and scandalised by the vulnerability you show that they get aggressive and act it out on you.

And as soon as you throw yourself—or your body—out there, it becomes political. In that moment, it is not my body any longer, but that of society, and that is why people act out things. The body is the focal point of all human experience, and when I take out myself, it becomes that of all of society. And that is what I usually tried to do with my performances—take myself out.

MS – Your use of sweat as a medium — both ephemeral and deeply personal — introduces a visceral layer to the engraving process. How do you see this gesture of imprinting the body onto copper as a form of storytelling or resistance?

MH – Copper is always in some kind of resistance, as it changes so much, and I see change as a rebellious act, that always, in some way, questions a status quo. And the sweat, yes, the sweat, that salty liquid that our skin transpires—it’s the respiration of our skin, the breath of skin.

Sweat, often seen as a mere bodily function, holds profound symbolic and mythological significance across various cultures. From divine creation to moral lessons, sweat appears in ancient tales, religious texts, and folklore, embodying themes of labor, punishment, and transformation. Brahma’s perspiration gave rise to a heroic figure. Just imagine this: it’s like it carries the essence of us, accumulated. It is so powerful that it can give birth to a creature, thus inscribing itself. It’s like the process of sculpting something with the waste of your body, making a sort of homunculus. We could speak for hours about this…

MS – Your work engages with time not just as a conceptual layer but as a literal material collaborator — from letting salt crystallize over six years to following a strict diet to tint your sweat pink for the copper engravings. How do you see time, patience, and bodily discipline functioning within your practice, and what kind of temporality are you inviting the viewer to enter?

MH – Time, time is such an interesting material in itself. The more we become acquainted with it, the more it becomes malleable. It really is like something tangible, at least it can feel like this to me, and of course, especially observing the works over time. One needs patience; things don’t happen overnight. Time acts with time. It’s a great lesson in patience and understanding that the more time my works have, the more they will open up. Like with the copper, the alchemists say that hidden inside metals are the hidden messages of the gods, and the more we work with them, the more those messages will surface. But of course, we are meant by this—the work we do on ourselves—to unravel the messages of God we carry, and for this work, we need patience. A psyche doesn’t change overnight; its habits and beliefs—it’s a process of unraveling layers over many, many years…

MS – Venice itself, with its dense layers of history and symbolism, often feels like a living presence — what is your relationship with the city, and how does the idea of the “Venice Daimon” manifest in your work for “Night Eyes”?

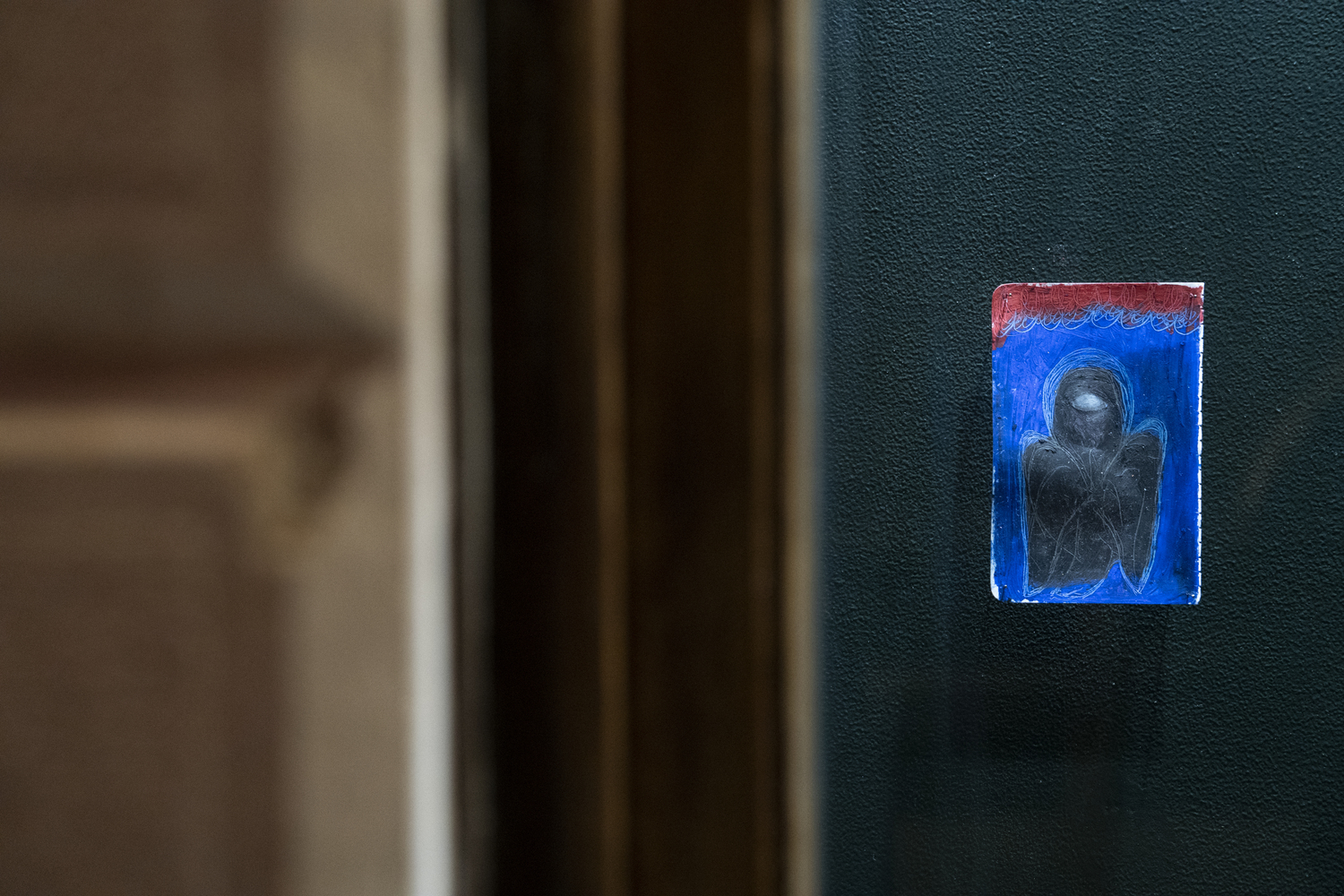

MH – Venice, this city is for me so ambiguous, and that is why I keep on coming back. It is not a place that shows itself just like that; it shows something—yes, its immense beauty and history—but beyond that lies something, something that is hard for me to put into words. But let’s say Venice has its own cosmology. Every time I come to Venice, I feel observed by something, a presence. And when you asked me to work on the window, I started to feel Venice again, and at one point, I drew it. The daimon I drew is a being that has it all: light and dark. It holds; it is powerful without wanting power. It protects in silence. It also holds your shadows. It doesn’t judge.

The etymological meaning of daimon is very interesting. I love etymology —as you know from the publication My Ocean Guide we did in 2017— and the etymology of the word made so much sense in relation to the drawing I made. The ancient Greek word δαίμων (daimōn) originates from the verb δαίω (daíō) or δαίομαι (daíomai), meaning to divide, distribute, or apportion. Combined with the agentive suffix -μων (-mōn), the term originally referred to “one who divides or allots”—a being responsible for distributing fate, fortune, or destiny. This concept is deeply rooted in the Proto-Indo-European language, deriving from the reconstructed root *dai- or *dheh₁-, which carried meanings like to divide, set, or place. Similar ideas appear across ancient languages: the Sanskrit word bhaga refers to a “distributor” or “god of fortune,” while in Avestan and Old Persian, baga also means “god” or “portion.” In Latin, the concept evolved into fatum—a “spoken decree” of destiny. In early Greek literature, particularly in Homer’s epics (8th century BCE), daimōn described an unseen divine force—less personal than theos (god)—that influenced human events. Unlike later demonized interpretations, the original daimōn was morally neutral, often ambiguous, and primarily symbolic of the mysterious forces governing life.