On the identity of your heart: an interview with Gao Bo

Gao Bo

The words “Il n’ y a pas de langue qui ne soit pas dangereuse” (There is no language which is not dangerous) are handwritten across the walls of the exhibition, could you expand on this? Is art not a language?

The words which I have written are in French, the words which I have used are a language, it’s not only an actual language, whether it’s in French or in English, these words are significant, they are the language of politics, the language of art and at the same time, I have rejected language. What I mean, is, that I would like to rediscover my own language, which avoids, for example, a question which, in my experience, people often ask me : “You are Chinese, so why do you write in French? And, on the subject of Tibet, why do you write in Chinese?”

I say to them: “What importance does the language have in reality? What I wanted to say has already been expressed in my work. Furthermore, it doesn’t matter what language you use, it is very difficult to find the ‘right words’. Sometimes you simply can’t write the ‘right words’. So I have decided to just write, and that’s enough for me. This is the writing I use in my work. I don’t need to reflect on which language to use, it’s my language.”

You spent the years from 1985 to 1995 in Tibet, where did this affinity with Tibetan Culture come from?

My connection with Tibet is quite particular, it is not connected with Buddhism, nor Tibetan Culture, nor the History and Politics of Tibet.

In 1984 Rauschenberg had a retrospective in Beijing at the Museum of Fine Arts. I ran into him in the exhibition hall and I asked him to sign the catalogue. At that point, I discovered that his next show was going to be in Tibet.

I wondered of what interest it could be for a great international American contemporary artist to show his work in Tibet. I asked him “Mr Rauschenberg, why do you want to hold your exhibition in Tibet?”

He replied “My friend, you know, all artists, like you or me, we try to aspire to the heights. Well, the Tibetan plateau, is the highest point on our planet. So I wanted to put my work at the highest point/altitude.”

On the one hand, I knew it was a joke, it was more about creating a dialogue around his work and with a culture which is different from ours and from others, as an artist, this dialogue was important. There were no museums, no galleries or buyers in Tibet. I think he was looking for a new source for his work and that is what made me want to go there.

So, I had a look at the map, at the time I really wanted to travel to a faraway country, all those years of studying at the Academy of Fine Art were stifling me. I wanted to travel abroad, but in China in the mid-80’s it wasn’t possible. So I said to myself “I’m going to Tibet” and that was my primary motivation for going to Tibet.

Over the years, a lot must have changed in Tibet and since 1995, even more so?

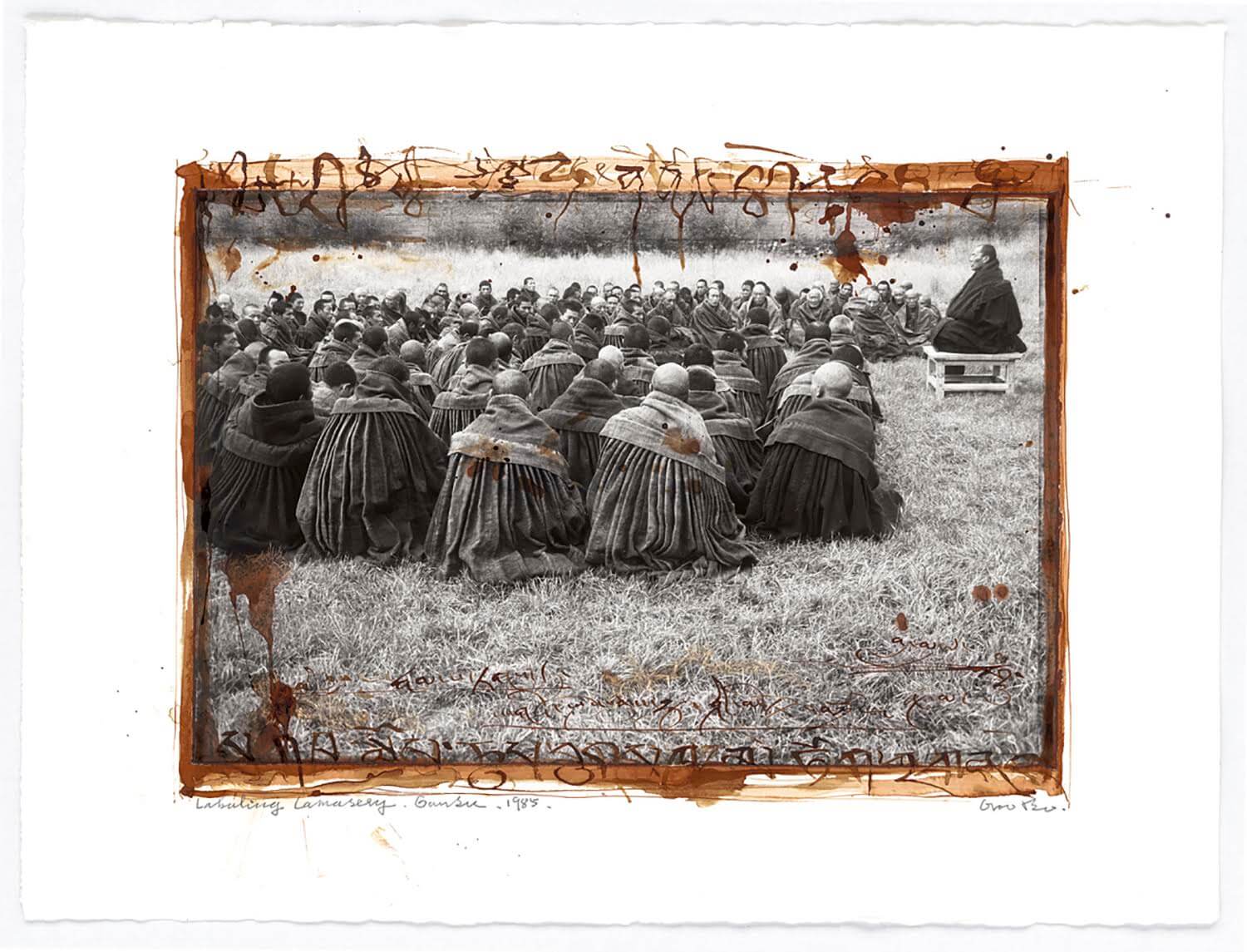

My last visit to Tibet was in 2011 in order to complete this installation. During the 10 years of travel in Tibet from 1985-1995 for my big book (The Offering), I developed a very strong connection with the Tibetan people and with their country. I created many friendships there. It’s a country, which in some way, remade me as a man. During these 10 years I learnt different concepts of value in our lives : the value of nature, the value of being human.

I lived in Tibet at a time when it still resembled something of the true Tibet, but unfortunately, today, due to ‘globalisation’ or ‘the free market’ everything has changed at an incredible speed. I understand, up to a point, that people don’t want to live in poverty, but what is wealth? They aren’t ready to understand or receive this wealth, which they didn’t formulate and which has been imposed in some way.

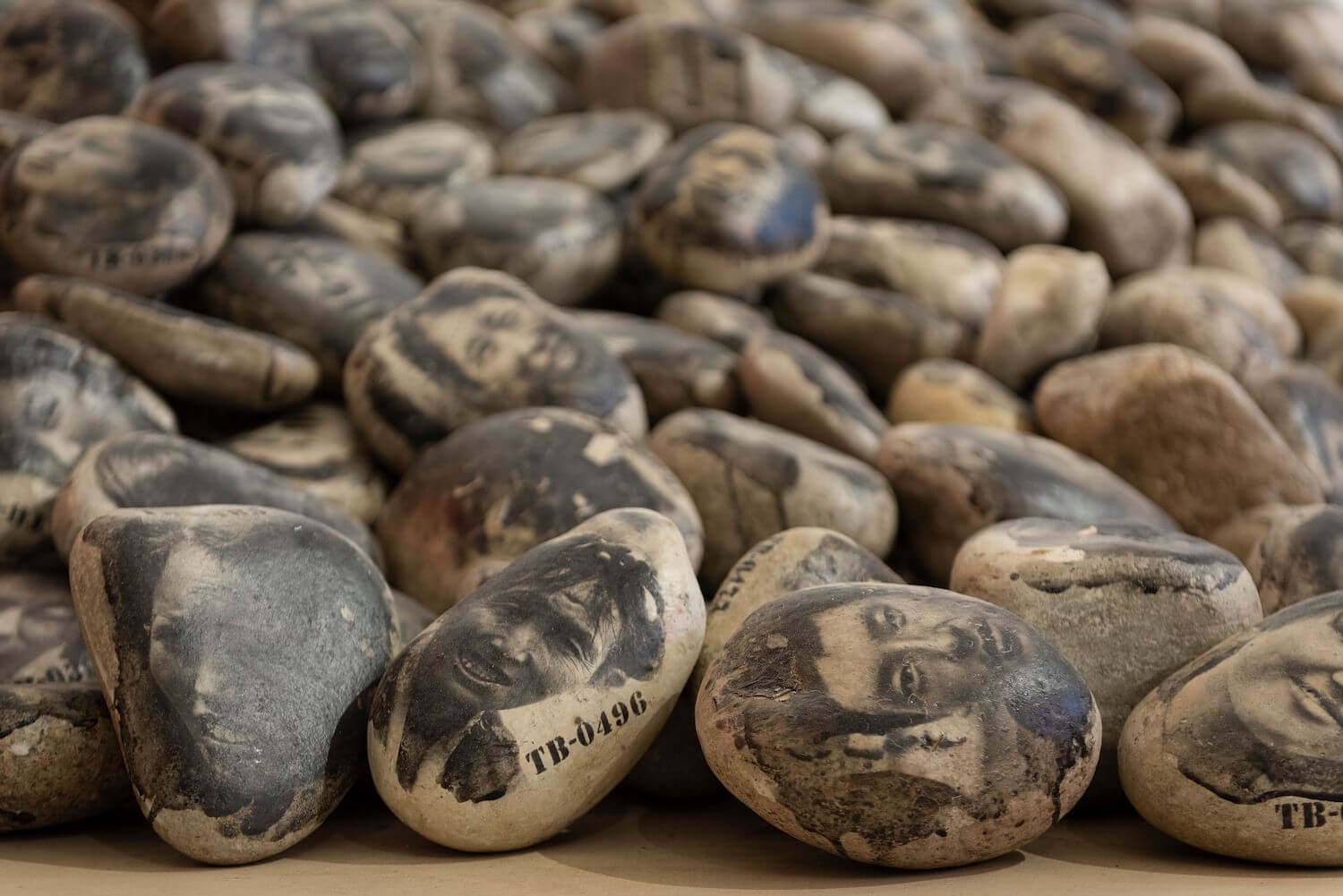

I have heard you say that you will go back to Tibet to return these stones, can you explain this and talk more about the 1000 stones?

To return the work (the stones) to Tibet and make it disappear is the end of a chapter, it signifies the completion of the circle. I don’t really want to keep this work, I would like it to lead me and others to a rebirth, that’s what I look forward to. Making the work disappear would be a powerful moment, although this work has taken a long time and been physically hard, I think it would be fine, I would rather this happened, than preserving the work in a museum.

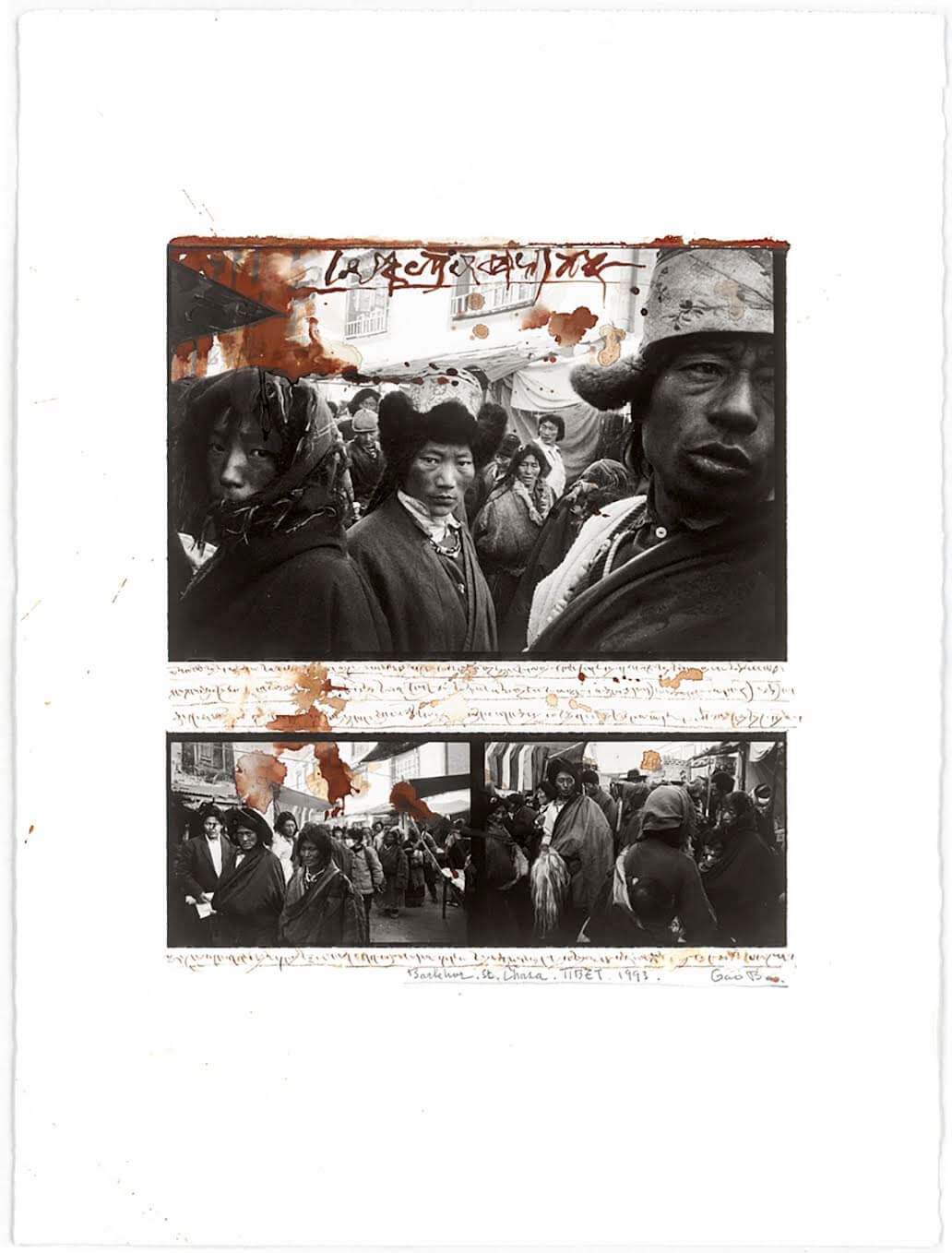

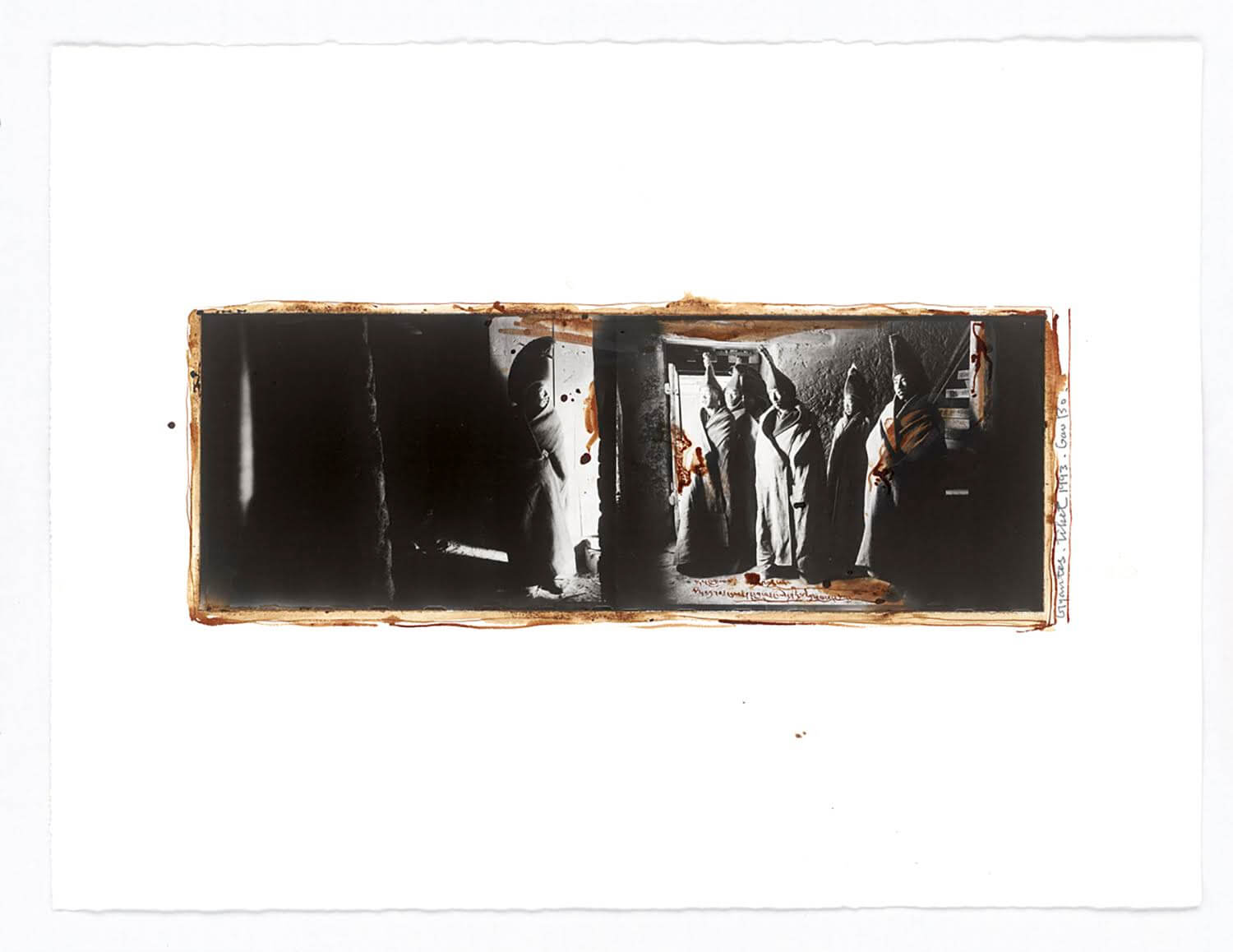

Regarding materials, I would like to ask you 2 things : about the use of your own blood on the photos? And about the use of neon, which I don’t associate with Tibetan Culture.

First of all, the blood is something which belongs to my body. To give my blood to a work of art like this, is not only to remind us of certain violent moments, but is also in some way a sacrificial gesture, I would like to be close to them, I would like to be side by side with them. The significance of writing in blood, comes from a very old story in Tibet. There was a great Tibetan master, who spent many years meditating in a cave on a mountain (I don’t recall which one) and I don’t even know whether it is a legend or whether it is true. One day the Master realised he had found the Truth, he had nothing to write with and he wanted to write about what he had discovered – this Truth, so he wrote in his own blood. For me, it is a similar gesture, because these photos are very bad quality. I left them in the drawer for a long time and I only rediscovered them many years later, so I made the same gesture. It sounds a little mixed up, but there is never one reason for a work of art, it’s difficult to give a single reason.

The neons represent fragility : it is fragility which gives light and hope and the neon emphasises this. In this work the neons in the shape of a cross, are also a symbol of the veins. This is a theme in my work I don’t know why, the sense of sacrifice recurs, at least in the time which I call my “Black Period”, there is a need to sacrifice in my work.

You’ve had a break from working as an artist for some time?

No, I have continued to create, but I haven’t shown my work. The work isn’t finished yet, so, when I am ready, I will show it. I have never stopped working. It’s nothing other than that. I would really like to emerge from this Black Period and into colour. I’m absolutely sure that the work I am making now will be in colour.

Could you tell me about your notion of identity, especially in regards to the 1000 stones?

The water creates the stones/pebbles, which is the originator of the stones.

It’s up to you to decide the origin, no one can impose it. You haven’t chosen to be English. We have the right to choose our identity in other forms.

When I speak about the originality of the stones, it is also universal.

As someone who works as an artist, we must allow ourselves to find an originality which goes beyond the borders of a country, which goes beyond the colour of your skin, which goes beyond the language which you speak. To be an artist, is also a privilege, to create our own originality, to create our own identity.

We talk a great deal about identity in this world. There are many people who feel they are denied their identity. I realise there is ‘official’ identity – but that’s another thing. I have an official identity.

For me, the important thing is the identity of your heart. I am a foreigner everywhere based on external appearances. Whether I’m in China or in Italy I am a foreigner. But in my world, I feel very strong and I am at home. That is good for me.

………the external world, perhaps it’s thanks to the language I use or the language of my art. It has been good for me.

Thank you, xie xie 谢谢