Salty Sermon: An Interview with Slavs and Tatars

Slavs and Tatars

Slavs and Tatars met over a decade ago, but have been working as a formal art collective for six years. Could you tell me about your editorial background and beginnings as a “reading group”, and your subsequent evolution into the production of works of art and own publications?

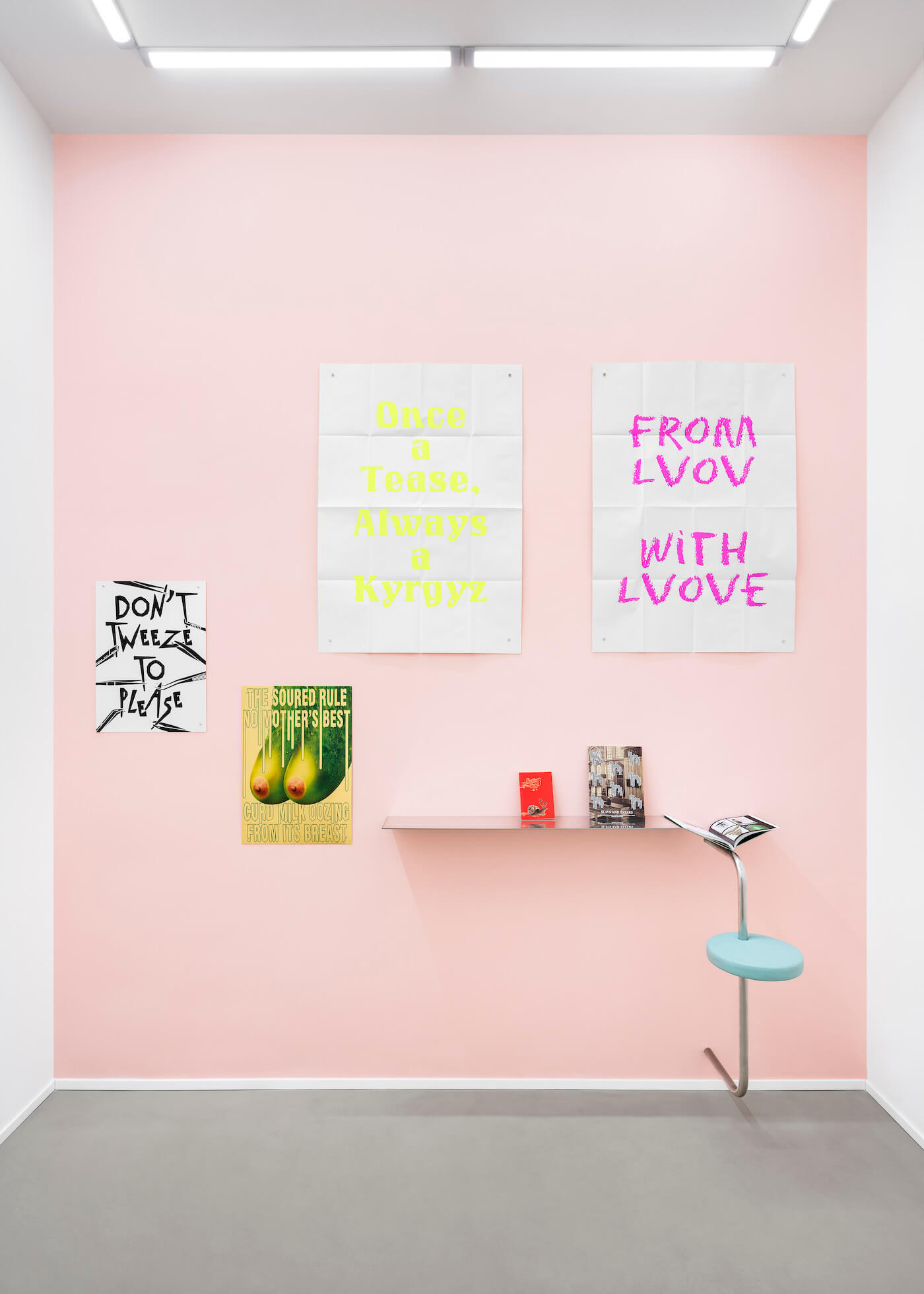

Because we started as a reading group, everything has always been editorially driven. Even when we started off with very modest budgets of 50 to 200 euros and were producing things, to when it became much more ambitious, with larger scale commissions and our work transformed into all other media. When we create an exhibition it’s always through the organising structure as if we’re making a book, with the crafting of the narrative.

Normally, the hierarchy in art is the expensive works that museums commission or galleries sell are the top of the pyramid and the further down the pyramid we go the more accessible things become, then at the bottom are the editions and print : books.

Although our work has moved quite far from books, we continue to publish – we’ve published 12 books in the past 15 years. People ask, why do sculptures, why do installation, why do furniture? This is our attempt to invert that pyramid so that all the expensive things that are being commissioned are actually props, or ways to bring people back to the book. This is not something galleries or collectors like to hear, or would agree with, but as far as I’m concerned the ultimate work is the book.

For many reasons; first of all I like the democratic principle of print. Our books are not art books in the sense that they don’t cost 2,000 euros each, they cost 30 bucks and you can order them on Amazon or you can print them off as a PDF, so it’s not an art book and it’s not a catalogue either – you won’t learn anything about us by reading about these books.

We often get asked why evolve into all these other media if you’re so interested in research and discourse, why even go there? The fact is that the geographic focus of Slavs and Tatars is not a deception, it’s not a mirage, but it’s not really only about this region, it’s almost like it’s a premise to talk about other things. One of the premises to talk about, is that there’s been too much of a focus on, especially in places like France, Sweden, this idea of knowledge as purely analytical, and what our region of the world allows is different types of knowledge – there’s emotional knowledge, there’s metaphysical knowledge, there’s digestive knowledge – there’s all these other forms of knowing and the fact is, the books are not the way to get there. I love books, I’m a reader, but through a book, it’s hard for me to have a phenomenological issue with the audience, and objects do that, installations do that, you have a spatial understanding of it, you might not understand what it means. Our books, they’re not concrete poetry, they’re normal text, it’s almost journalistic, you could say. Any decently educated person can understand our books. That’s the point. There’s no Derrida and it’s not e-flux.

The role of the art is, in my opinion, to disarticulate and that’s very hard to do. I say that even about our own work, I would say that 10% of our work successfully disarticulates because disarticulation doesn’t mean to stay silent, it means to undo. So the best analogy is that you’re spend months stitching a sweater – the book is your sweater, you’re stitching it, you’re composing the discourse, the story, the images, and the art has to be that thread that undoes exactly what you just stitched. That’s hard to do because it’s hard to undo what you just did – consciously. It doesn’t always work, often you try and it feels forced.

I don’t want to sound mystical, but there’s something alchemical about when you still don’t get a work that we’ve spent years thinking about. If you get it, it’s not really a good artwork.

Tomorrow you will be presenting the lecture-performance Transliterative Tease at SPRINT, could you expand on this exploration of the potential for transliteration as a strategy of resistance and research?

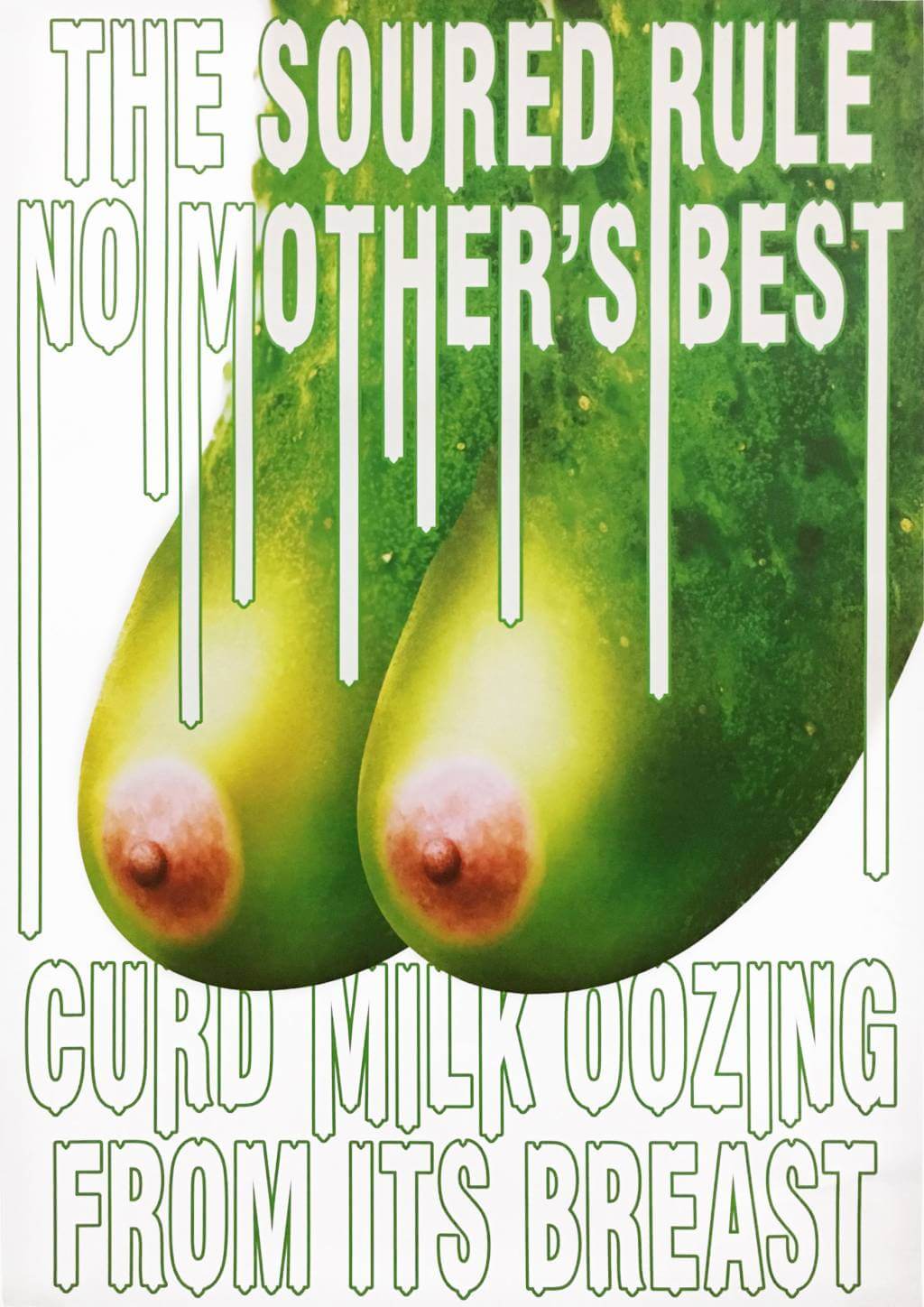

What’s interesting about transliteration is that it is something we call a ‘stupid phenomenon’, and fermentation is in fact that. Basically what we mean by stupid phenomenon is a very simple thing that people don’t consider to be deep or substantial, but actually there’s quite a lot of things wrapped up in there. There’s a work we did early on called a Mono Brow Manifesto about a monobrow, and we’ve done things about pickling. These are very good examples of what I call ‘stupid media’, in the sense that there’s nothing simpler than cabbage and water and salt, it’s basic, right? But through fermentation, you can talk about questions of everything all the way through to the enlightenment legacy of binary thinking, of transmogrification. But because we’re dealing with a part of the world, which is so, as you’ve said in your questions, overlooked, we’re very aware that our audience doesn’t give a shit about our region.

In the West, which is where most of the art world still takes place, putting aside the fact of the rise of multipolar art worlds in China and the Arab world, the fact of the matter is the West is still king in determining what is considered important art, historically and market wise.

So because the West is still that driving force, most of the audience doesn’t care about syncretism in Central Asia. They don’t give a shit about Lviv University’s Department of Orientalism that we devoted a couple of years to. So these ‘stupid media’are ways for us to engage people, with things they normally wouldn’t be engaged with. If we were doing work about stuff that everybody’s already thinking about – artificial intelligence, income inequality, the environment – then we wouldn’t have to make such an effort, we wouldn’t have to make pretty things. There’s a lot of artists who just make things that are really challenging formally, they don’t look like candy, like our artworks, but because our subject matter is so obscure, we have to meet our audience halfway. Otherwise, nobody’s going to give a shit about it. We can’t turn our back on the audience and expect them to come to us!

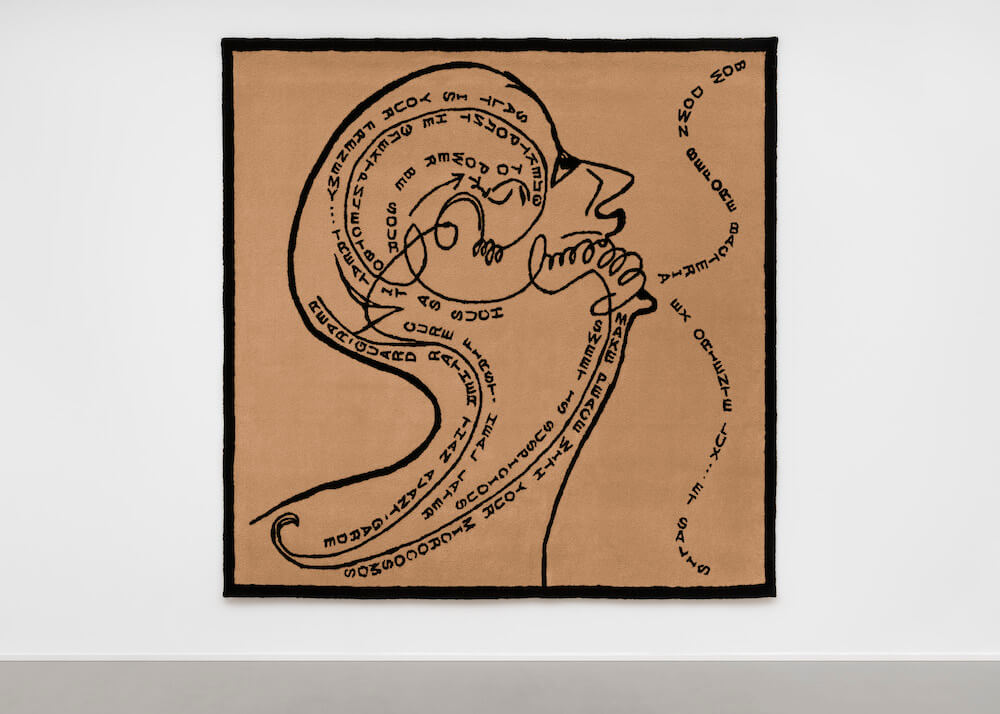

So transliteration is a good example of that because it is essentially something that people who speak other languages, that are not Latin based, are doing all the time, but we don’t think about it. There are departments devoted to translation, it’s considered noble. Nabokov did it, Edgar Allan Poe did it, but nobody thinks about transliteration because it’s not transactional and yet there’s armies of ideologies that go into why alphabets are changed. We think of alphabets as being naive and innocent, it’s normal that you and I use A, B, C, the Roman alphabet, it’s normal that Iranians use the Arabic alphabet, but there’s no such thing as an ‘innocent’ alphabet, alphabets accompany empires in the same way that the Latin alphabet came with the rise of Christianity and then in the last 500 years became a symbol of secularism.

So in fact, the Soviets at some point, even though they Latinised and cyrillicized all the Muslim subjects, they themselves were considering whether to Latinise Russian at some point because Cyrillic was considered to be too corrupt. It was far too imbued with Orthodox Christianity and for them in the early 20th century, in 1917, Latin was secular and Cyrillic was Christian. There’s a very interesting episode where the early Zionists, largely European Jews, were planning to draft Hebrew as a daily language. Until then, Hebrew was a liturgical language, and all the Jews of Europe used the local languages for their secular for their daily transactions, Hungarian, Polish, Russian, German, et cetera and when they went to Palestine, they resuscitated Hebrew as a daily language, there were many people who believed actually it should be written in Latin script to distinguish it from the liturgical one. So the holy language of Hebrew would be using the Hebrew scripts, but the secular and profane, would be Latin, it didn’t happen, but there was a quite a robust debate about it.

Slavs and Tatars exhibitions, lectures, and books primarily fall within one of eight research cycles. How did this organising principle come about? And could you briefly summarise each of the eight cycles?

It didn’t really come about consciously until halfway through 2016, when we did a mid-career survey taking stock of 10 years – and the reason we did that is we wanted to understand that the world had changed a lot from ’06 to ’16. The cycles are essentially ways for us to organise a principle. So some cycles have a book and a lecture attached to it, and they all have works. They are ways for us to come back to them.

So the Friendship of Nations Cycle is about the relationship with Poland and Iran from the 17th century to 21st century. It started in 2009 and went until ’11 heavily, but then we went back to it in 2019 to make some works that were part of that cycle. It’s really fascinating, there’s uncanny similarities between Catholicism and Shiism, that was part of what came out of this research into the relationship between Poland and Iran, is that not only the countries have some weird convergences, but also the faiths, in the sense that both Catholics and Shias have this idea of 12 apostles. Shias have 12 Imams, we have the same Imam who comes back at the end of time on the day of the judgment, just like Jesus.

‘Kidnapping Mountains’ is a celebration of complexity in the Caucasus, this cycle investigates the linguistic, social and political phenomena of a region at the site of historical crossroads between Ottoman, Persian and Russian empires, this one doesn’t have a book related to it, but it has intellectual moments. They all have works, of course, related to them.

So ‘Régions d’être’ spans the unwieldy geographical remit of Slavs and Tatars – between the former Berlin Wall and the Great Wall of China – while also serving as a prequel to the collective’s practice. ‘Régions d’être’ is the collective’s term for an area that falls between the cracks of history and general knowledge: largely Muslim but not the Middle East, largely Russian speaking but not Russia, and having a complex relationship with the nation. Yet rather than representing a specific value, history or culture, this ‘region of being’ is as much an imagined, poetic geography as it is a real, political and historical geopolitics.

Language Arts is also the thing that goes through all of our practice and unteases the politics of alphabets: the many fraught, attempts by nations, cultures and ideologies to ascribe a specific letter to a sound. The book ‘Khhhhhhh’ (Moravian Gallery, Mousse / 2012) examines, literally, the throat as a space of phonetic and sacred agency via the Hebrew, Russian and Arabic letters for the fricative [kh] while ‘Naughty Nasals’ looks to the nose, as a ‘site of resistance in the Slavic and Turkic languages’.

With Pickle Politics we’re actually moving out of this for the first time. So this is since 2016 and we’ve been working on this for about five, six years since 2016 and we’re doing a new cycle which we’ll be showing in 25′. We don’t know what what it’ll be called yet, but it’s not really related to any of these things.

I’m intrigued…

In 2019, at the 58th Venice Biennale, curated by Ralph Rugoff, we presented 15 different vacuum form plastic panels in the Central Pavilion. They’re all about transliteration, they’re all using the wrong script for the texts featured, the wrong alphabet. This is the only body of work that is in reference to art history, to Marcel Broodthaers, the latter half of the 20th century’s equivalent of Marcel Duchamp and his Poèmes Industriels. Why Broodthaers is so dear to us is that he was a poet and a writer until he was 35, he was only an artist for 10 years of his life and he’s considered to be one of the most important conceptual artists in the world – he had done a whole series of vacuum form plastics like these, called Poèmes Industriels.

Broodthaers, spent the last four years of his life creating this fake museum called the ‘Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles’. It was considered to be the first work of institutional critique, the first time that the museum is critiqued as an institution of cultural value. He does it in a really very conceptual way of presenting reproductions of artworks, crates that are empty, but all through the eagle – the eagle being a Western symbol of power and empire.

We’re going to translate this massive project into our region, replacing the bird with the symbol of a Simurgh, a mystical bird that you find all across our region. If the eagle is heteronormative and imperial, the Simurgh is gnostic and rather gender-nonspecific.

The Simurgh is famous, due to a story – the Persian equivalent of a Homeric epic – called the Conference of the Birds by Attar; all these birds go looking for the Simurgh, a symbol of God, of the transcendent and the real Truth. Some of them get lazy, some are too vain, some of them don’t really want to. At the end they finally reach where the Simurgh lives, there’s only 30 of them left. There is a castle with a courtyard yet there is no Simurgh, there’s just a pond where their own reflection is shown. It’s a play on words in Persian, Simurgh literally means 30 birds. The idea is the transcendent or God is inside of you, you should stop looking for it elsewhere.

So that’s what the next body of work is going to be about .

It has taken the full scale invasion by Russia of Ukraine to make the world realise that Ukrainians have their own distinct language, culture and character. I think it would be fair to say that most people have a very hazy understanding of who the Tatars are, their origins, culture and suffering. Can you tell their story in a fairly succinct way?

We’re glad you asked the question because in all humility, our best work thus far is our name. “Slavs and Tatars” has this ambiguity and complexity that is really at the core of everything that we try to do. Tatars was a term that was used by colonial and Western orientalist explorers who traveled to the east, they used this term as an umbrella term for all the brown people who they didn’t know where they came from. So imagine in the 16th and 17th century there were people travelling east, such as Marco Polo, and they basically knew who Arabs are, they knew who Turks are, and they knew who Persians are. All those other people : Dagestanis, Azeris, Turkmen, Uzbeks, Kyrgyz they just called them all Tatars. So essentially, it was a racist term. It’s like when they used to call Muslims ‘Mohammedans’. It’s just a catchall term for everybody who’s brown from that part of the world.

Now, to make it more complicated, of course, there are real Tatars, there’s Crimean Tatars and there’s Volga Tatars. So there’s the Tatars of the Volga, which is where Kazan is in present day Russia and then there’s Crimean Tatars in Ukraine. They both use the ethno name Tatar, and yet they’re not at all linked to each other ethnically.

So the dummies guide answer to your question – what’s the short history of the Tartars?

The way I explain it, is that, essentially, they were the descendants of the Mongols who created this massive empire. They were the subcontractors, the cousins who were responsible for Western parts of the Mongol empire.

Part of the reason why we’re so interested in this region is that it misses all the Venn diagrams. Everybody nowadays in memes uses Venn diagrams. Our part of the world misses them all, especially Central Asia if you think about it. Because Central Asia is largely Turkic peoples, everybody except Tajiks are Turkic people, Turkic languages are spoken in that region, Uzbeks, Kyrgyz, Turkmen, Azeris, Dagestan.

Yet they were never under Ottoman rule, they’ve been under Russian or Soviet rule. They’re Muslim, but they’re not in the Middle East, they’re mostly in Asia, but were never part of the Chinese Empire, except for Xinjiang and Uighurs. So they don’t check all the boxes and that’s why it’s interesting, it’s a fundamentally multiconfessional region.

Salty Sermon at eastcontemporary focuses on Pickle Politics, could you expand on how practices and symbolism of fermentation, can construct a political argument using notions of the rotten?

The social contract that underpins a lot of European societies, is that the government is the provider of our wellbeing, especially in northern Europe, it’s paternalistic or maternalistic. That’s why the baguette has a certain price ceiling in France. It is this idea that the basic needs of our lives, the social welfare state, the government provides for that, and it’s often very maternalistically provided – in the sense that we are the children of the republic. So we wanted to show that if we are the offspring of this land and we are the children of that republic, then the nourishing milk or the milk that we’re feeding at the breast of our republic is actually rotten, it’s kefir.

What’s interesting about the idea of fermentation is that it’s a form of rotting which is not necessarily a bad thing – you’re rotting to preserve, so in itself it’s counter-intuitive, you’re not preserving to preserve, you’re managing the decomposition. So fermentation has allowed us to talk around subjects that we normally avoid. We’re very loathe to talk about politics because we think that too many things are happening too quickly. We can’t talk about things that are happening today, you have to let things settle and so this allows us to talk about it in a way which is not direct and understand it in a more nonlinear analytical way. The question is what are we bringing to the table that activists, journalists, scholars are not bringing? And I would say that the artist’s role is to not ask the direct question, is to not tell the story. We have to undo these very clear lines of investigation in some sense. We scramble the story.

Talking of Pickle Politics, could you tell me about Pickle Bar?

Pickle Bar is our Slavic aperitivo bar-cum-project space where we invite artists, writers, thinkers, amongst others to consider the limits of language. Launched in 2020, we’ve run public programmess about queer language, socialist children’s books, or more recently costumes and textiles in times of collapse. About four or five years ago, we reached a point where we were receiving more commissions and more requests than we could deal with. It’s admittedly a privileged position but what most artists do usually is grow vertically. You make more expensive works, or you work with more expensive producers. That was never the intention of Slavs and Tatars, so we thought, how can we go otherwise? So we launched the Residency Programme for Young Professionals from our region and Pickle Bar shortly after that – for me, they’re both linked in the sense that they are ways for us to continue the investigation and the things we’re interested in without it being contingent upon us, individually or collectively as S&T.

It should be obvious that when you’re a collective, that it’s not about you personally, but you would be surprised. At the end of the day, the commissioning body wants you personally to do a lecture, to draft a text etc. In a way we were able through Pickle Bar to share all our resources to allow other artists to continue the line of thought we are interested in but by letting others do it. Slavs and Tatars are the MCs in the space, if you will, we never perform at Pickle Bar, we just do the scenography, we’re the hosts and the same with the residency – it was to help people from our region who don’t have the opportunity to attend real art schools.

It wasn’t planned, but what’s been great is that both initiatives allowed us to reclaim Slavs and Tatars as a platform as opposed to being the name of a certain amount of individuals. Now art institutions don’t talk to us in an infantalising way. Institutions engage with us on an equal footing. How can you help us? How can we help you? They’ve also understood that all this Art with capital A only represents about 50% of what Slavs and Tatars do. There’s curating, publishing, lectures, public programmes, residency, merchandising : which until recently institutions considered an afterthought or mediation but they’re not, they’re integral projects in their own right.

We essentially function as a small scale institution.

And to be honest, we’ve never been fans of wine and cheese: it’s a rather rubbish way of drinking. We much prefer clean spirits and fermented items. The Slavic way of drinking, pure vodka and zakuski, is a lot healthier. The logorrhea about oenology drives me mad. I really don’t want to hear about it. It’s like coffee culture. Give me a break. Give me a good cup of black tea, like a Turk might give you. Turks don’t talk about bubble tea and this tea and that – they just give you good strong properly brewed Ceylon tea. There’s something very basic about vodkas and spirits and the idea was to create a place where we could just have fermented items and vodka as opposed to anything else.

I am a fan of MERCZbau, your multilingual Merch range, could you expand on how garments can shape new forms of politics, memorialise difference, and forge new communities against a backdrop of political, economical and ecological collapse?

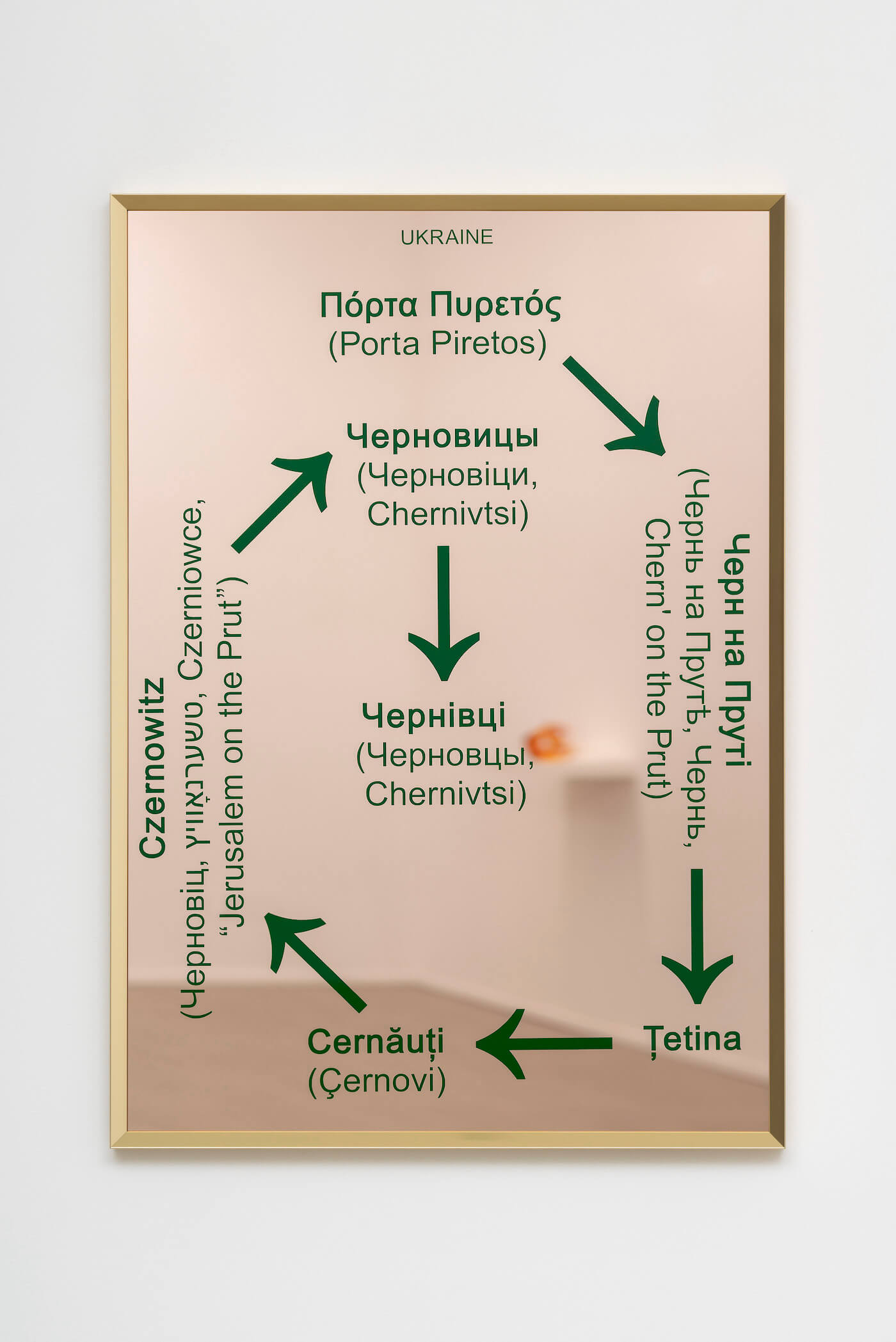

We first presented the merch line in Wrocław at OP ENHEIM and Chicago at the Neubauer Collegium. Are you familiar with the history of Lviv and Wrocław? Poland lost Lviv, their eastern most city, after WWII to the Ukrainians, and they gained Wrocław from the Germans which became their western most city. The Polish population of Lviv was transplanted, or leap-frogged across the whole country to Wrocław

Lviv had a very important Oriental Studies Department until the Second World War. As the eastern part of the Polish nation, perhaps it made sense for the Poles. Very important Mongol and Sanskrit studies were being done there and when this population transfer happened, if you look today, you dig a bit deeper into the Wrocław University faculty, most of the departments can be traced back to Lviv. But Oriental Studies didn’t survive, so this didn’t get catapulted, whether it’s because it’s all on the Western edge of Poland and not the Eastern Edge and they thought they didn’t need it. I don’t know. But Lviv University was shut down during the entirety of the Soviet Union, which is insane and that tells you everything you need to know about occupation, when an entire university of a massive city for 50 years is closed and when it reopened, now they have the Oriental Studies Department running again – this is way before the war, before the full invasion.

We basically resuscitated this department in Wrocław and we asked teachers of Lviv University Oriental Studies Department to come and teach Poles – Persian, Turkish and Arabic. But imagine they’re Ukrainians teaching Persian in Polish and, for me, it was a sophisticated way of trolling the Poles. Until the 2022 Russian invasion, the Poles slightly looked down upon the Ukrainians, who were seen as manual labourers, Uber drivers, restaurant workers. The Poles didn’t consider the Ukrainians as intellectually as cultured as them and for us it was a way to show actually that the Ukrainians are much more sophisticated and cosmopolitan than Poles, who are 99% white Polish Catholic, and here you have people who are Tatars, Armenians, Jews, Greek Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, Ukrainian Orthodox, Ukrainian Catholic – it’s far more heterogenous.

So we imagined this speculative merch, this stupid American idea of every university having its merch and then there are even sections for the cousin of a Stanford alum. It’s rather ridiculous – so we thought, what would the autochthonous merch of Lviv University look like? The problem now is even European universities, Cambridge, Oxford, Amsterdam, they all recreate the American merch.

If Islam hadn’t lost the battle of modernity against Christianity some 500 years ago, what would our version of Harvard University merch be like in this part of the world?

One of the lectures we do is actually about Slavic Orientalism, how the East looks East, we always talk about Orientalism, the British and the French looking to the Muslim world, but how does Eastern Europe look to the Muslim world?

The sad thing is that Islam was translated through the colonial enterprise of Russia, but actually if Islam had been translated through Ukrainian or Belarusian, it would be more accurate to the original Arabic (as they share sounds which don’t exist in Russian).

We’re very proud of the merch, even though it doesn’t make us any money and doesn’t go into museum collections, but there’s just as much intellectual density in a pair of trousers as there is in an artwork. But for whatever reasons, as we know in our milieu , they will never be considered as important because they are a piece of clothing. The conception of it is just the content, the discourse is just as rich. It’s not a problem. That’s why we’re doing it. But it pains me sometimes to know that they’re not taken as seriously as something which is put on a pedestal – and it doesn’t make sense to put it on a pedestal.

My grandfather was from the region of Lviv, and before the full scale invasion I spent many months in this incredible city, a city at the crossroads of thousands of years of complex history, yet very few people have even heard of it, it has been left off the map, why do you think this is?

I think the reason why this region is generally overlooked is that it doesn’t fit into the ways that we’ve been brought up to think of nation, faiths. Nothing is single in these places, it’s so torn, right? Even the Polish thing, now. Ukrainians like Poles, but we also know that Ukrainians are suspicious of Poles because of their history. Poles were the oppressors at some point as well. Now they’re friends, but it wasn’t always that way.

In general, I always believe that it’s always at the edges of things that the most interesting things happen. Edges of empires, edges of ideologies, edges of religions. The reason why we do this whole syncretism of Central Asia is that what’s amazing about this part of the world is that Muslims are praying to petrified mulberry trees. Now, that’s the most heretical thing for an orthodox Muslim, for whom the most important creed is the unicity of God. But in Central Asia, it’s often pantheistic, if not animistic. Because they were on the edge of the Muslim world, they were in touch with Buddhists and Hindus and shamans. They incorporated these thoughts, these belief systems – that’s what makes it so rich, this incorporation of the other…

What’s interesting about syncretism is that you’re not only bringing other peoples, other spaces into your space, but you’re also bringing other times because those belief systems come from another stratus of time. So it’s a layering of time as well as space and that’s what’s so fascinating. I saw this amazing exhibition in Kraków maybe eight years ago, about Galicia and I didn’t know anything about this, but Galicia was the oil producing part of Europe until the early 20th century. So all the oil of Europe for the lamps was coming from this part of the world. So it was the Saudi Arabia of that era. So that just tells you already how coveted it was and why Lviv looks so rich and looks so ornate, because they had the money.