The Story of a Mountain, The History of a Country: An Interview with Minerva Cuevas

Minerva Cuevas

Could you tell me a little about the work The Story of a Mountain, The History of a country, the ideas behind it and the significance of the use of Tezontle as a material?

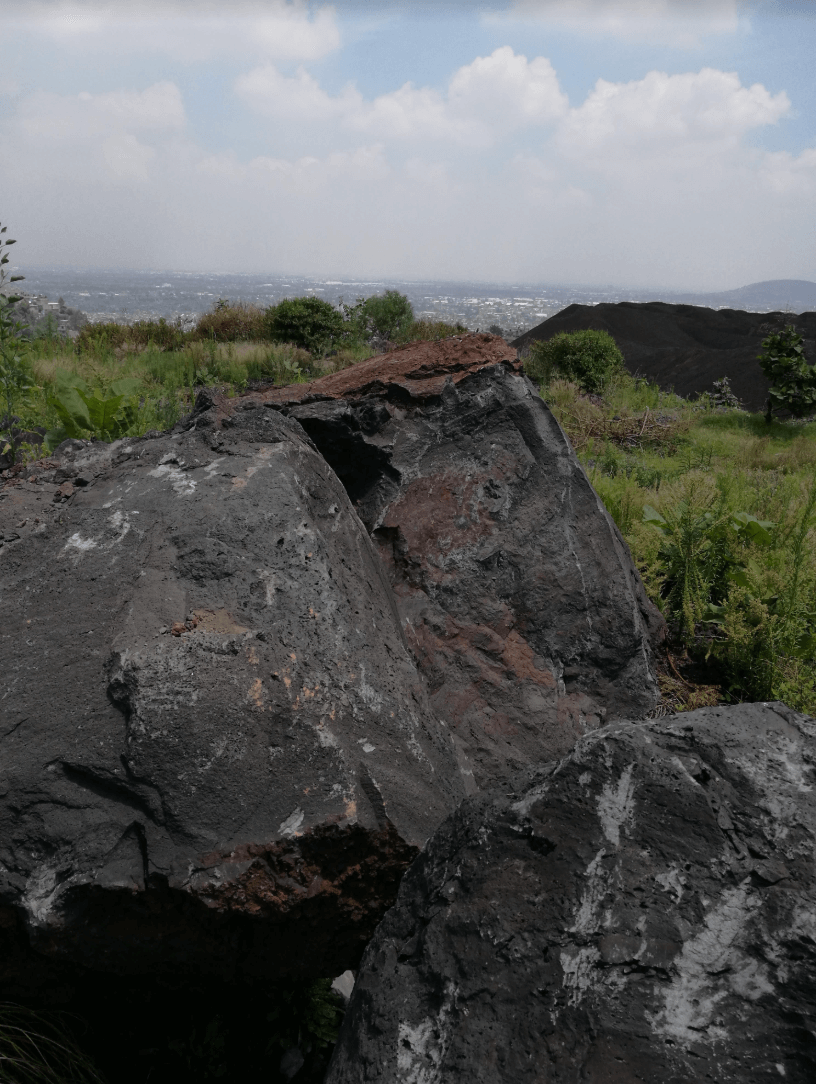

The material Tezontle (a volcanic rock used extensively in the construction of colonial buildings, in Mexico) is important as a connection between the prehispánic and colonial histories of Mexico. In prehispánic times, Tezontle was used for the construction of the House of the Eagles in México-Tenochtitlán, known today as the Templo Mayor, structures such as these were taken apart and the material used for colonial architecture.

Tezontle is a material linked both to volcanic eruptions and the element of fire. I am also interested in the cultural aspects of fire, in regards to the destruction of libraries or book burning but also fire as an element necessary in the generation many natural processes, some seeds, for example, require the need of fire to germinate. So the starting point of my research was initiated by fire, from there I began to explore the volcanoes around the city which connects to my research of the oil industry in Mexico and the writings of Ezequiel Ordoñez. Ordoñez was a geologist who in 1901 participated in the first survey of the oil regions in Mexico, along with a Mexican commission who after inspecting decided there was no oil and nowhere to drill, Ordoñez thought otherwise and separated from the group. Eventually, thanks to his profound knowledge of the surrounding geography, he made the first commercial extraction of oil possible. Ordoñez wrote numerous articles and essays on archeology and the history of oil in Mexico which informed a great part of my initial research.

Through this next exhibition and the use of this specific material, I want to pose the question of how we think about the connection between human and land. What is the place that concepts like subject, power, alterity and ecology occupy? And is there a possibility for a social space that is linked to nature.

How will your research manifest itself for the exhibition?

I am bringing a two tonne boulder of Tezontle, it is basically a monolith which is rare to find as Tezontle is usually broken down as sand or small fragments for construction, so an entire monolith is rare. These areas resemble Mars landscapes, and they can be found just on the outskirts of the city.

Flanking the boulder of Tezontle there will be two glass panels paintings depicting slogans I created. I reference a poem by the Peruvian poet Blanca Varela who was better known in the 50s’. Her poetry is dense with meaning and precise in her choice of words and expresses the world from inner space’s point of view, this was something I wanted to draw on and refer to in this project. The other panel is connected to migration with the slogan – ‘Migration is Natural’, which is very general but connects both with the animal world and the current crisis we have in the southern border. For the glass paintings I draw the typography as I have done in other artworks.

Your work is underpinned by a socially and politically engaged research. What are your thoughts on the notion of artist as activist?

Nowadays there are elements shared between art and activism, but l disagree with that particular notion in connection with my work, I don’t think it is useful to generate categories that marginalise certain kind of practices. I think it is necessary to make a clear distinction, as I am familiar with both areas – contemporary art production and social and ecological activism. With activism you have the ability to evaluate and measure the results of campaigns or have very specific objectives. On the other hand, the most important and enjoyable aspect of art production is the freedom to generate projects and artworks using endless formal solutions without the need to measure any results. There are no parameters for that. That’s part of the freedom. It doesn’t mean that art is not capable of being linked to social change, it totally is.

Did your work take on a political slant from the very beginning of your career?

If I’m correct, you studied visual arts but then quit – why was that?

I started interventions and performative work quite early on, without realising at the time that that was what it was. So really, throughout my career I have had this connection to intervention strategies. Initially I was mainly interested in developing video projections and video sculpture, there were not any classes in video production or contemporary art and perhaps that was part of my disappointment at the time with the art school. The bureaucracy of the whole educational system didn’t work for me and I just started developing my own work, so that made art school secondary and not worth it.

You founded The Better Life Corporation in 1998 as a means of exploring the politics of contemporary hope and with the goal of achieving public good by means of art practice. Is it still running? If so how has it evolved over the years?

It is still running and has become somehow an autonomous entity, independent of me as the author. Mejor Vida Corp. started as a response to the urban context of Mexico City, distributing anonymously free things around the city, like seeds or subway tickets. It provides everyone with ways of exercising agency and subverting the system through acts of ‘micro-sabotage’. Then I started producing student ID cards, to give everyone the benefit of a regular student discount. I also lowered the price of some basic products at the supermarkets by changing the barcodes on the labels. In general it was response to the institutional and economic elements around the city in order to find gaps.

Both your work and your background is very much rooted in Mexico. What is it about the city that inspires you and what is about it that frustrates you most?

I am not usually led by inspiration, my work begins by developing strategies and research depending on the context I find myself in, but of course Mexico City has been a big point of departure for me, both for its past and the social mix. The city is centralised within the country, so a layer of rurality pervades the city, this is one of the main attractions for me. It is also the political stage for the whole country, everything has to go through Mexico City. I am also very familiar with the south of the country and the rural areas there, such as Oaxaca and Chiapas.

What frustrates me about the city? The increasing number of cars and some noise pollution.

Where is your research taking you next?

I am developing work for Mediacity Bienniale in South Korea, the research I am doing at the moment is mainly connected to natural resources and I’m specifically looking into mushrooms, the ecological importance and the social structures connected to them.

Could you give our readers some insider tips as to where they can get a taste for true street culture and community life in Mexico, away from the usual beaten contemporary art track?

My studio is in the historic centre so around there I would recommend the Abelardo L. Rodríguez market where there is one of Mexico City’s most interesting mural collections, rarely visited by tourists. Enormous mural works are part of the bustle of daily market life. There you can find works by some of the students of Rivera: Ramón Alva, Pablo O’Higgins, Antonio Pujol, Ángel Bracho, Pedro Rendón, Raúl Gamboa, Miguel Tzab and American artist like Isamu Noguchi and Grace Greenwood.