Art After the Hangover: Daniel Baumann on the Changing Art World and the Power of Audience

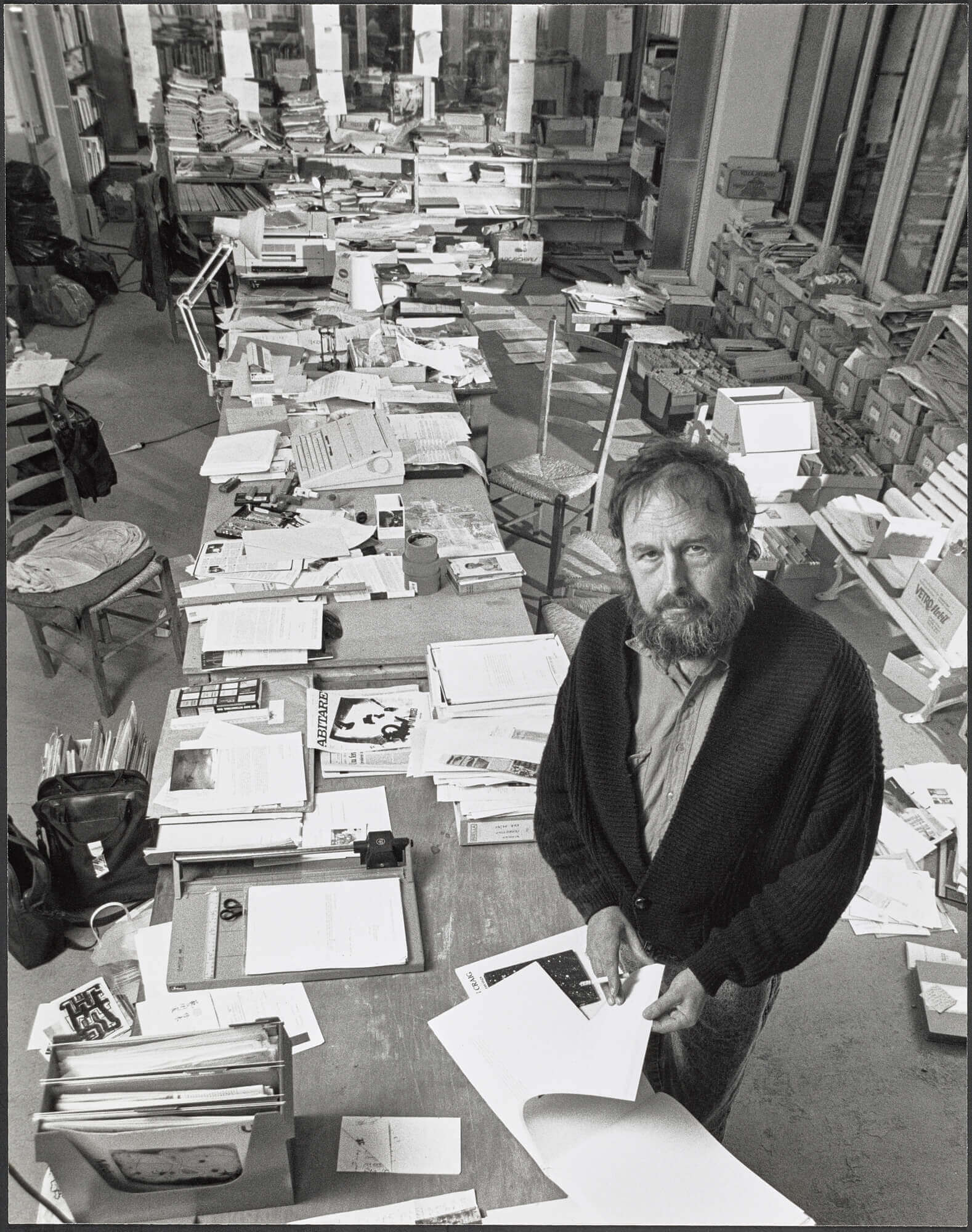

Daniel Baumann

Daniel Baumann reflects on his ten years as director of Kunsthalle Zürich in this wide-ranging conversation with Mara Sartore. Touching on the history of Zurich’s art scene and his experience with New Jerseyy in Basel, Baumann offers a critical but hopeful portrait of an evolving art world, and the enduring need to speak to an audience beyond the bubble.

MS – You directed the Kunsthalle Zürich during a time of significant transformation, both locally and globally. Looking back, what would you consider the most emblematic moments or curatorial decisions that defined your tenure?

DB – That’s a good question. Maybe the fact that I was able to do whatever I wanted. I mean, if I had the money, of course. But, back in the days, I applied with this idea. I sent a letter and said, if I become the director of Kunsthalle Zurich, I will put the institution under a stress test. Because I thought the landscape of art institutions in the world had very much changed in the previous 20 years. When I started to get interested in contemporary art in the mid 80s, it was a small world – mostly European and American. And then it got bigger and bigger, and more and more commercial. In the 80s, it was maybe 500 people really into contemporary art in all of Europe – a couple of galleries, some collectors, some art critics, and artists. And then it turned into this global phenomenon with thousands of galleries, biennials, art fairs, collectors spending a lot of money on art. The Kunsthalle used to be a place to promote contemporary art that wasn’t shown very much. But in a time where museums sometimes do projects like independent art spaces, where galleries are doing shows like museums, where art fairs look like biennials and biennials like art fairs – I asked myself, what is the role of Kunsthalle today?

And so I started with a programme that did all sorts of things. All sorts of exhibitions. I did an exhibition on the history of playground. Once, with American artist Rob Pruitt, we transformed the Kunsthalle into a church – the students from the Theological Faculty held Sunday services there. I did also more classical shows with Albert Oehlen, Liz Larner, Christopher Kulendran Thomas, Peter Wächtler, and Phyllida Barlow. But once in a while I would do other projects, trying to find out what the role is in this new world that we’re still living in. And the Löwenbräu building where the Kunsthalle is located, is a unique place containing a top gallery like Hauser & Wirth, the Migros Museum, a corporate collection, but also Luma, a private foundation, smaller but still excellent galleries like Francesca Pia, or the Museum Haus Konstruktiv and VFO, an association promoting the art of printing. It is a broad mix.

I somehow discovered the public. I thought, all of a sudden, why do we all do what we do? It’s obviously to promote art and artists. But actually, even more important is to engage with an audience. And that’s why I did all these different exhibitions. Then I worked with the theater and with dance companies, because I thought there’s a lot of people out there who are interested in culture, in art, they’re very curious, they’re very open, they go see dance performances, they go see thematic exhibitions, they go see singular artists – and I want to talk to all of these different publics, all of these different audiences. The important experience was definitely to engage with the audience, without knowing who the audience is.

MS – And during these ten years, did you investigate who your audience was? Any research to understand who was visiting the museum?

I never did formal research, because I somehow thought I believed in the curiosity of people. And interestingly, some artists who were completely unknown – like Pippa Garner or Levan Chogoshvili, a Georgian artist – attracted the largest crowds. People think you have to do blockbusters exhibitions, but the audience works in a different way. When there’s something they hear about, they come.

We did once do a study, one of those audience analysis reports. The most interesting takeaway? What attracts the most people is not social media, or the press, or newsletters. It’s word of mouth – one third of visits are due to people telling their friends, “Go see this, it is interesting”. That explains how unknown artists became some of the most popular shows, because their work spoke to people. You never know, you may think a famous person attracts a lot of people, but not always. That was an interesting experience to have, that showed that there is a very interested audience out there in the city. And if you talk to them, they will come. But you have to talk to them. You can’t just talk to the inner world of the art world. You can’t just talk to the bubble. You have to figure out also a way, through education, mediation, text, so it speaks to more people.

MS – Zurich is often seen as a solid yet subtly reserved art scene. In your view, how does the city reflect or contradict the dynamics of the international contemporary art world?

DB – Zurich has historically been a very conservative city. It has had this moment of Dada, yes. But from the 50s to 70s, it became very conservative. Then in the 70s and 80s, young people, and young artists started to revolt – among them Bice Curiger, Peter Fischli and David Weiss, and others. They created a whole new movement in the city of young people doing alternative projects, spaces, art, being active. And out of that scene developed a gallery scene. And then with this massive influx of money at the end of the 90s, when collecting became fashionable, in five or ten years, Zurich became a very important place for galleries. Here’s where Hauser & Wirth started, Eva Presenhuber, Mai 36, and more. Now there are at least 10 top galleries in Zurich, and 20 more of high quality.

This created a very strong art scene in Zurich. Mostly through galleries, but also through a mix: galleries, the Kunsthaus, the Kunsthalle, the Migros Museum, the Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Luma Foundation, the Museum für Gestaltung, artist-run spaces, two art schools – ZHDK and the alternative F+F.

The complete spectrum, a perfect mix of small, mid-size, big, private, commercial, non-commercial, institutional, educational.

MS – And what about the Zurich Art Weekend? Its first edition was in 2018 when all this spectrum was already in place, right?

DB – A few years ago and initiated by Scipio Schneider, Charlotte von Stotzingen and others, a group of people met to promote the weekend before Art Basel. We wanted international visitors to spend some good time in Zurich on the weekend before heading to Basel on Monday. You have to be attractive, so they built a programme – talks, parties, dinners, openings, guided tours, VIP programmes – and gathered all the information on a website, a booklet, social media and so on. Charlotte von Stotzingen is the magician behind it, and it has really been growing a lot. I could see it in the numbers: at first we may have had 1,000 visitors, now it’s closer to 4,000 for a weekend. And obviously, art people like to spend money. It brings cash into town – restaurants, taxis, bars, shops are happy.

MS – What about the current state of art in 2025? You described a trajectory of growth, from the 80s to the 2000s. What is going on now?

I think a hangover is going on. On the commercial side, it is more difficult from what I hear, and there’s also more critique coming from inside the art world. I think there’s been a reversal. In the 80s and 90s, when you were into contemporary art, people would look down at you. They would say, “My kids can do it better. This is some stupid stuff. I don’t even understand what it is”. Then came the money. All of a sudden we, the weird ones, became the cool ones. For a short moment, for a couple of years in the early 2000s, everybody was at the table: curators, artists, collectors, galleries, institutions, all discussing things, enjoying the success and being being proud. But then it really commercialised further. And I’m critical about it because I think it turned into a neo-feudal system with gatekeeping through money.

MS – Do you think it was like a bubble, a speculation? Or is it just a fashionable movement that is still going on? Is there something new coming up?

I think a reversal happened. Before, we were unified because the enemy was outside, it was the “bourgeois society”. Today contemporary art is accepted by the mainstream, people go to galleries, Kunsthalles etc. But now the critique comes from the inside: gender, race, diversity, neoliberalism, commercialism, professionalism – all this is from the inside. People are getting very critical about it, they say contemporary art is for the 1%, it’s only for the rich. From being the strange ones, now we are like the decoration of the rich. So, the outside, the general audience, is curious, whereas the inside is very critical about a lot of things.

MS – It is also very challenging to understand which artist is going to survive. Is this established only by very rich collectors, on what they and their advisors like?

DB – In the 60s, art critics – Achille Bonito Oliva or Pierre Restany or Clement Greenberg – would say, “this is an important artist”. Arte Povera or Les Nouveaux Réalistes were created by a critic. Then, from the 70s, the curators became more influential – Harald Szeemann, Jean-Christophe Ammann, Rudi Fuchs, Kasper König. People would say, “that’s a Harald Szeemann artist”, or “that’s a Celant artist”.

MS – And now it’s the turn of big collectors like Pinault…

DB – Exactly. And now you say, “that’s a Pinault artist”, “that’s a de la Cruz artist”, “that’s a Rubell artist”, right? Just by the way people speak, you can see the shift. When the money came in, the galleries and the collectors became the gatekeepers. And I think a bigger shift happened. The critic or the curator, they had to argue why this and this is important. There was still some kind of intellectual effort there. And it was still there around the 2000s, but then the market took over: the simple fact that you would put down a million or 200,000 or 50,000, it makes it valuable. The fact that you put down the money was the argument.

At first, it felt good – we had money and we were fashionable. But now I think we’re all a little bit shocked by what it produced. So there’s a hangover moment. And some people pull out. Creative minds that used to go into art, now go into tech. But I think it’s an interesting moment for the art world because hopefully it will lead people to talk more about art again, and not just about everything else.

MS – Don’t you think that if on one side there is a hangover, on the other there is also the need – of those who are intellectually engaged in the art world – to go back to the meaning of art? Contemporary art begins with Marcel Duchamp, when art is conceptualised as a ready-made, anything can be art, and that art has no longer a function. But in the crisis and confusion of the contemporary world, maybe we are going back to seeing artists like the real prophets of the society, art as the only way of representing the world and the artists as the only ones able to understand what’s going on…

DB – Or create a meaningful moment in your life.

MS – Exactly. To interpret the present moment, because it’s so difficult to understand what’s going on. I think of Anne Imhof at the German pavilion, it was really striking.

DB – Well, you mentioned Marcel Duchamp – it was an emancipatory movement, people could emancipate themselves, be different and discover a new freedom, a new space through contemporary art. And nowadays I think that emancipatory moment has shifted or has partly been lost. I think it will come back, but we have maybe been seduced by the money a little too much.

MS – Going back to your career, you have also been involved in the Basel art scene with the independent art space New Jerseyy. Can you tell me about this project? And how does the art scene in Basel differ from the one in Zurich?

DB – The difference is that Zurich is a bigger city with a bigger art scene, and more galleries. Basel has a just a few. New Jerseyy is a funny story. I was running a public art projects in Basel, financed by the city, and they wanted to use art to animate a neighbourhood that was a bit damaged. There I saw this empty store, and I proposed to my board to not just do wall paintings or sculptures, but to rent this space and give it to young people so they could run it and bring life back to the neighborhood.

I approached three guys that were running a magazine, a fanzine called “Used Future”: Emanuel Rossetti, Tobias Madison, and Dan Solbach. They were around 20 years old and were mostly into the graffiti scene and fanzines. Dan was a graphic designer, and the other two were artists. I had facilitated a project by them during Art Basel, presenting their fanzine “Used Future” at Ecart’s booth of John Armleder. So I got to know them, and I thought they were very interesting, energetic, and irreverent. I had a budget of 40,000 CHF and I said they could use it to run the place. They agreed, but only if I joined too. I was 20 years older than them, but I said yes.

From 2008 to 2013, we did 12 exhibitions per year, every month an exhibition, so it was very fast. The openings were always packed. People would come even from Germany. It was a lot of fun, we would drink beers, hang out. We brought in all sorts of young artists – it became this place where galleries started to look for new artists. But that was never the goal. We just wanted to do shows and enjoy art and discuss it.

MS – Were there any famous artists who started their careers at New Jerseyy?

DB – One or two, maybe. But towards the end, I was working in Pittsburgh, and some had left, but Emanuel, he did a show still in New Jerseyy with Anne Imhof, for instance. And then we did Kerstin Brätsch, a German artist. We did a show with Rob Pruitt, but he was already well-known. We did one with John Armleder. And then a lot of young artists who were then shown here and there. It became a scene.

MS – For my last question: what would you recommend seeing in Zurich in 24 hours?

DB – I haven’t seen everything, but there are a few highlights. There is a show on Franz West’s early works at Galerie Eva Presenhuber – pieces from the 70s and 80s, many of them I’d never seen before. I think that Klara Lidén at Kunsthalle is really good. I went to see Suzanne Duchamp at Kunsthaus Zurich. Very interesting. I knew her work from the more Dada period, but she has very surprising later work.

And then, I mean, everything here is interesting. Chinese artist Bing Wang at the Migros Museum. Markus Raetz, a legendary Swiss artist, shows at Galerie Francesca Pia. Everybody is pulling out their best shows right now, because the international crowd is coming, and you should honour that. If people come to Zurich, maybe they take two extra days – so give them your best.