Paris is like Ithaca: the home to return to – an interview with Adel Abdessemed

Adel Abdessemed

This interview opens the first printed edition of My Art Guide Paris, could you tell us about your relationship to this city and whether living and working here has influenced your work in any way?

This question about Paris is perfectly fitting because I am in the middle of setting up my next exhibition at Galleria Continua, in the heart of the Marais, a stone’s throw from the Centre Pompidou and the Museum of Art History of Judaism. I have many memories in this neighbourhood. I am reminded of Azzedine Alaïa singing Oum Kalthoum in the kitchen where we spent so many endless nights drinking and talking. I also remember one particularly intense night: the Spanish themed evening spent in the company of my friend Christophe Ono-dit-Biot at the Picasso Museum.

As soon as a city starts influencing me, it means that I enter into conflict with that city in general. I say this in a Baudelerian sense: Baudelaire was in conflict with Paris, with its cafés, with its elite, with the state, with everything. Courbet was with the communards. Today everything is against everything. In a globalised era, in the kind of ‘general brothel’ in which we travel, all cities influence me. From one city to another it is sometimes only one or two hours, or at most a twenty-four-hour flight, so in this context where everywhere is close by, everything influences me and touches me. Talking about an influence in a specific way is therefore a bit tricky for me. Sometimes my heart is there, but the body is absent.

We know that you are a nomadic artist: over the years you have moved between Paris, London, Berlin and New York. Why did you decide to settle here? What do you think of the contemporary art scene in Paris? How have you found it different from other cities you have lived and/or worked in?

France is the country of my second birth, it is my adopted country. I am anchored here. There is a very strong relationship that makes me think of Homer: Paris is like Ithaca, it is the home to return to. In this sense Paris will always be Paris, but there are also other very important cities; like beautiful Tel Aviv, which I miss. I have never lived there, but every time I go I feel part of the heart of this city.

One of the reasons I moved to Paris is that my children go to school here. But I, in truth, live in Paris like a hermit. I live in an imaginary time. I hardly ever go out: I am always in my studio, surrounded by my books, my cellar and my vinyl records. I listen to music and work when I feel like it. I listen to a lot of music because it is vital and I don’t want to die before I have listened to all my countless records. And because everything influences me, it is very difficult for me to talk about this or that particular aspect of a city I have lived in.

Finally, to answer your other question, there are artists in Paris, but I don’t think there is a Parisian scene in the strict sense. The big news in Paris is that there are more and more big private foundations, which I think are detrimental to the life of museums.

I would now like to talk about your artistic practice: how much do current events and politics count in the realisation of your works?

This is the context in which I live and work, so it is crucial. When I deal with politics or art, I take the Freudian direction, the psychoanalytic route, one could say. Hence my reflection on the role of censorship, self-censorship and repression, three instances that artists must always be aware of. Our dreams, for example, can be deceiving: we must not say, see or think such a thing; so we hide them from ourselves. Whereas my task is, on the contrary, to face them. Politics is a daily bombardment, literally and figuratively. Not to mention everything related to my intimacy, my childhood, my memory that is killing me…. Death is never the problem. The problem is life and therefore it is politics.

Flaubert was censured for Madame Bovary, which is an exceptional book. But he won the case. Art will always remain the exception through which we confront politics and morality, which proceed by condemnation and censorship.

Artists, the real ones, do not worry about censorship because they have the freedom to provoke. But I do not live in systematic confrontation with society. I can be free, even beyond the struggle for freedom and what is forbidden. In my case, I have many works that have been censored. “Why?” one has to ask why. Sometimes it is because I touch on a subject that politics does not bear nor dare. There is also the question of the law, what is forbidden, what is allowed. I have been faced with different forms of censorship: moral and legal… Sometimes it was about nudity, the issue of animals or the issue of violence. In the United States, I did a piece called ‘Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?’. There they can hunt wolves and kill them. In France, the law categorically forbids it. From one country to another, things change and this can affect the reception of the work. But art cannot be reduced to these questions. By instinct, intuition and imagination, art can touch wonderful, extraordinary things. Those who do not support it will always want to banish it.

I read in an interview that for you the role of the artist is “to fight without playing the victim or the executioner”. Can you tell us what the term “fight” associated with your artistic practice means to you in this case, and who or what you are fighting against?

I cannot imagine an art in which there is no combat. When Caravaggio models a prostitute to paint the Madonna, it is a fight. The cardinals of the time liked the work, but the people wanted it destroyed. For once, it was political power that protected the art. When Michelangelo launches himself into the battle of the Sistine Chapel, he is seventy years old! It is a total challenge, both in rivalry with other artists, but also against himself. The strength or power of art and creation comes from all these tensions.

Through these examples, I am simply saying that it is natural that the artist fights and that art is a struggle.

You can be considered a versatile artist: you use different mediums, including sculpture, photography, video, painting, etc. to make your works. Which of these medium do you prefer and which seems the most intimately connected to you? Which communicates best with the audience and expresses most immediately what you want to express?

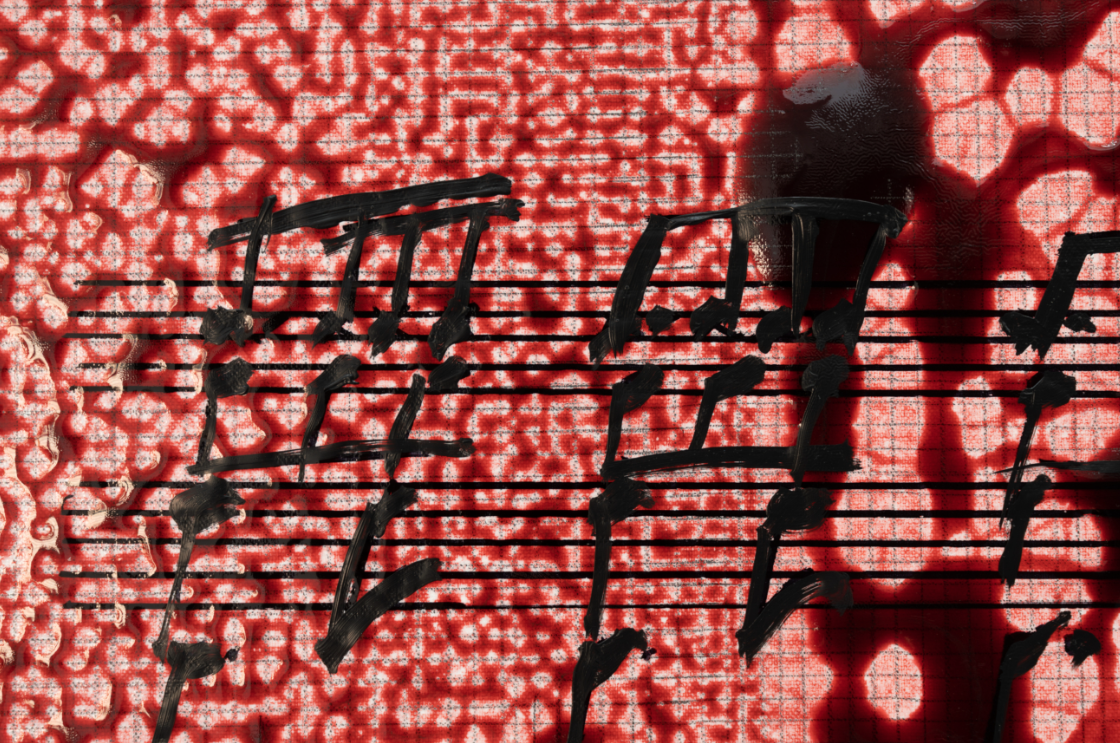

The most deeply rooted and intimate medium for me is drawing. I am dyslexic and drawing is my first language, a primal form of writing. Matisse said that drawings are paintings made with reduced means. It is true: in a drawing there is everything. Drawing is like breathing. I become like a fakir walking on hot coal when I draw. After that, yes, there are all the other mediums.

Are you working on any projects at the moment?

My most important project is exhibiting at TAMA, the Tel Aviv Museum. Freedom, sharing… I see in it a kind of rediscovered motherhood: my birth in Constantine, my childhood in a Jewish home, a Berber mother of Muslim faith who gave birth to Christian sisters who were midwives… I have the impression that I have gathered the gods of monotheism and that I will discover this trinity.

Could you suggest some useful tips on Paris for our readers? Could you disclose some of your favourite places in the city and for someone visiting the city, what do you think they should absolutely see?

For me Paris can be summed up like this: it is an open book, an extraordinary history book for anyone who wants to read it, of which every street is a page. Crossing some of the streets of this city where Lacan and Gainsbourg used to walk…. Crossing the Boulevards des Maréchaux, I think of Diderot when he was in prison and Rousseau visited him. I think of the banks of the Seine, the Quai des Grands Augustins, where Picasso painted Guernica.

I also have a taste for wine and restaurants and we are lucky to have some of the greatest chefs in the world here. It is extraordinary. I can recommend going to my friend Pierre Gagnaire, for example. Tasting his cuisine is like experiencing a work of art. Whats more, Pierre loves life as much as art and that is also why I designed a work for him on the ceiling of his restaurant Le Balzac.Yet in the end I barely move, I stay in my studio, I walk around my neighbourhood, from there I see the whole planet. For me, a tiny piece of Paris turns out to be the manuscript of the world.