RojoNegro: Practicing Indigenous Knowledge in a Turbulent Present

RojoNegro

Mara Sartore – Your collaboration began almost ten years ago. How did it start, and how has working together reshaped your individual practices over time? How do your different backgrounds, sensibilities, and research processes interact within the duo – where do they converge, and where do they generate productive tension?

RojoNegro – Although we formally began collaborating ten years ago, our collaboration may have started even before we met, but it truly began to take shape when we met twenty-three years ago. At that time, we were two young people, seventeen and eighteen years old, dreaming of becoming artists. We spoke constantly about art and were feverishly seeking to see, experience, and live art through our limited yet valuable possibilities in Morelia, Michoacán. We have grown together enormously, both personally and professionally. For twenty-three years we have been in conversation, searching again and again for that precious moment in which Art exists. Our individual work corresponds to our personal histories, which find parallels in social processes and whose struggles are interconnected. Our collective work is a moment of joyful exploration, where the results of our personal investigations – both intellectual and aesthetic – are poured out to accompany one another in our struggle in art and in life – struggle which consists of fighting for a world of equity and peace, where every being and their inherent knowledge are valued and respected, so that we may rejoice in the richness in which we exist. Our formative life stories, as well as the historical burdens of our ancestors and our bodies, may differ from one another in many ways, even coming into opposition at times, which undoubtedly generates tensions between us. We learn from these tensions every day, every day we see how we can use our wounds and our scars to continue striving toward the world of peace we want, the one we know begins with ourselves. Learning is our primary tool. We seek to learn every day from one another, and a great deal from others well. We observe, experiment, fail countless times, and try again. We firmly believe in the practice of peace and in sustaining hope, and we seek daily to learn how to do so. All of this practice distills into our artistic production.

MS – The name RojoNegro refers to Mesoamerican cosmologies in which the cardinal directions are associated with specific colors and geographies, pointing to your respective ancestral lineages: Noé Martínez’s Huastec origins in the East and María Sosa’s Purépecha roots in the West. How does this connection between territory, ancestry, and color inform your understanding of identity and collaboration?

RN – As we were saying, although we have collaborated formally for ten years, it was not until 2022–2023 that the name RojoNegro emerged. We suddenly realised that it was confusing for audiences to understand when we were working as a duo, so we were advised to give a name to our small collective. Choosing a name that identified us both was a major challenge. It was a difficult task, so we focused on the points where we meet as a duo, two of which are fundamental: a search through the body and a search through the historical past. This inevitably leads us to territory – the territory we inhabit and the territory where our ancestors live. Both of us, deeply fascinated by the idea of the pre-Hispanic tracing of the Universe and its organisation into the four cosmic directions or cardinal points, thought to use these as a reference to situate ourselves in the present through our past, within the multiple layers of time that we embody. It was then that we realised that the Huasteca region of Mexico, from which Noé’s family comes, corresponds to the color Red, while María’s region of Michoacán, in western Mexico, corresponds to the color Black.

This discovery deeply excited us, as it drew a line of connection to the importance of red and black inks in pre-Hispanic times, to the symbolism of sacredness they contained, and, in turn, to the responsibility they carried: to continue “the rule of life” – a metaphorical phrase that implies continuing the knowledge involved in the search for cosmic balance between human beings and all other existing beings, what today can be linked to the Zapatista struggle for “buen vivir”, as well as to the struggle for ecological and social well-being. In this way, everything aligned perfectly with our purpose. Thus, carrying the name RN becomes for us a double action: remembering and honoring our ancestors, and struggling, from any territory, to preserve the rule of life as a possibility from our present-future.

MS – Red and black (rojo y negro) also recall the sacred inks used in codices and vessels to mark cosmological thresholds – between the visible and the invisible, the material and the immaterial. How do these symbolic systems shape your approach to the body as something capable of moving across different layers of reality? Within this framework, how do concepts such as nagualism and tonalism operate in your practice – as lived experiences, conceptual tools, or methods of research?

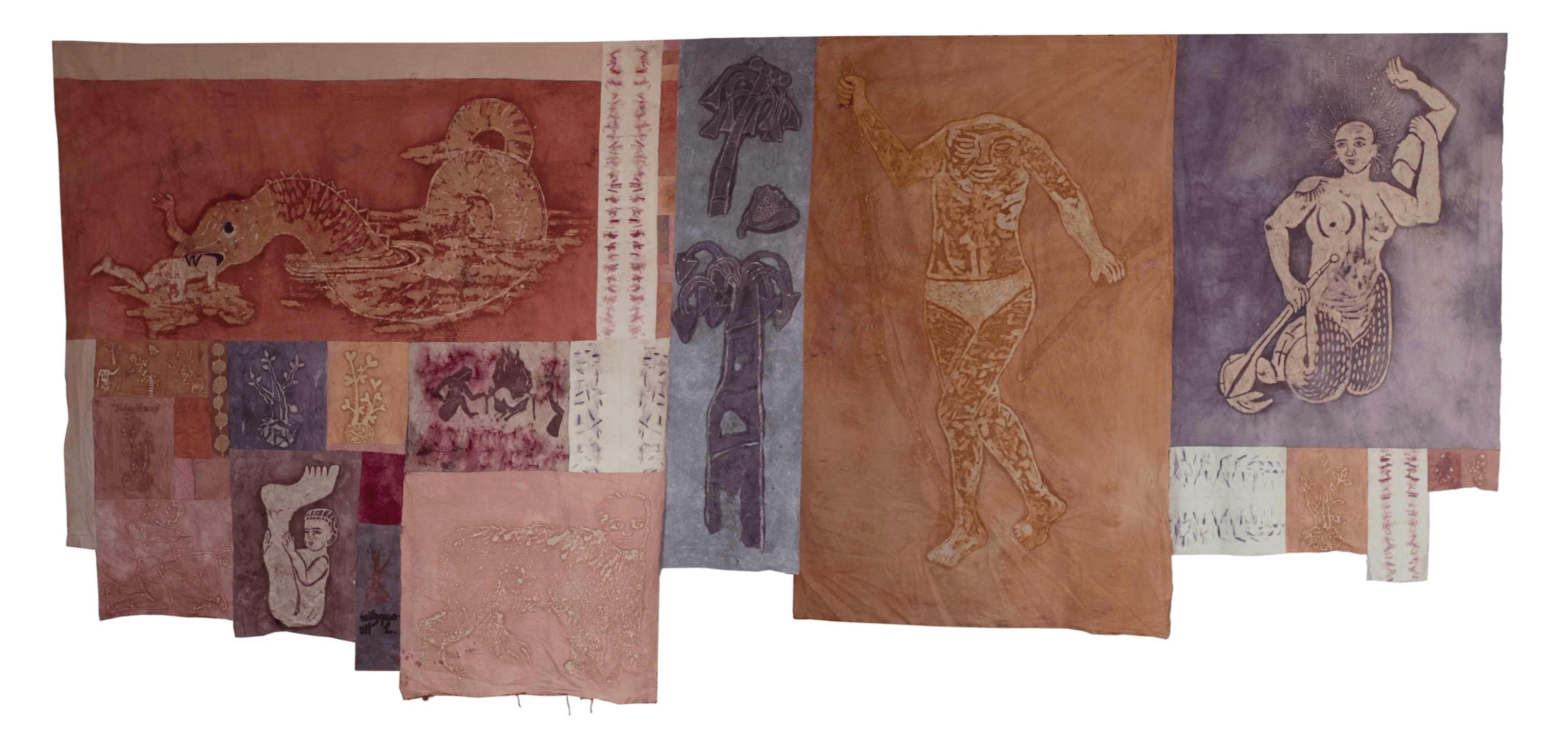

RN – RojoNegro’s practice focuses on recovering the ancestral knowledge of our Indigenous peoples, whether through experimental archaeological research, bibliographic anthropological research, or what academics call fieldwork, in order to employ these forms of knowledge as tools for conceptualising both art and everyday life in the present – an alternative path to the one proposed by the monocultural, colonising capitalist system.

For us, pre-Hispanic art from our Americas is among the most refined expressions of conceptual art that exist, since both materially and formally, artists materialised philosophical and ontological concepts into powerful and sublime metaphorical systems. Thus, the continuous learning and discovery of these teachings can be brought together with the reassembly of fragments of knowledge from before the invasion, along with the documentation of what has survived and is still practiced – both within our communities and within our seemingly disconnected bodies – as a proposal for a form of contemporary art that responds to the intellectual and sensory needs of our turbulent present.

Our Indigenous peoples’ ways of seeing and understanding the world provide alternatives for resolving or addressing problems of contemporary life. For this reason, our practice is a constant experimentation in giving these concepts a sensitive, embodied form, in such a way that they can awaken the audience’s interest, as well as their own connections and creative possibilities. Mesoamerican concepts of Being and the body offer us, first and foremost, possibilities for self-understanding, while also acting as creative triggers that we can deploy across multiple planes, sometimes as methods of creation, sometimes as models for research, and at all times as a permanent laboratory within our bodies and everyday lives. The Mesoamerican understanding of Being implies the idea of a multiple being: that is, a subject composed of several entities. We could say that each subject is a community, an ecosystem that includes even other external bodies: animal, natural, mineral, and energetic bodies. For us, it is through this understanding of the body that we can dismantle the individualism and selfishness encouraged by the prevailing extractivist systems that are destroying the balance and health of both the Earth and ourselves.

MS – In your work, the body often appears as a site of multiplicity and contradiction, inhabited by different temporalities and presences. How does colonial history and its ongoing effects enter into this understanding of the body? Do you see your practice as a way of reactivating silenced forms of knowledge or of addressing historical and personal wounds?

RN – We are subjects born in a territory where cultures and histories were fractured and subjected to attempts at eradication through all kinds of violent processes. Within our bodies dwell the records of past ancestral convulsions, as well as present ones; but likewise, our bodies also carry surviving acts – that is, acts that safeguard, or are themselves remnants of, the knowledge that others sought to erase.Our bodies grew up within coloniality, within the aspiration to the dogma of Western civilization, yet our grandmothers gave us herbs when we fell ill, and in dreams our ancestors told us of sacred matters as well as of their journeys across the Earth, even though we did not understand them. We began to research in order to understand, because we carried broken, heavy, and angry hearts, and we did not know where all that discomfort came from. We began to research in order to find the link from which this chain of afflictions originated, and we arrived at the moment of colonial invasion and at how its methodologies of violence persist to this day, now exercised by ourselves. A remedy had to be found, and so we began to re-educate ourselves in the knowledge of our Indigenous peoples and we saw the importance of placing this knowledge in the body, because colonisation had been inscribed in the body in order to become everyday life and a world system. In the same way, the cure must be inscribed in the flesh, so that it too may become everyday life and, eventually – so we hope – a world system.

With slow steps, after many years of practice and experimentation, we have gradually worked through imposed fears, begun to understand our histories, listened to the voices of our ancestors in dreams, and slowly healed our hearts – though there is still immense work ahead. We cannot do anything for the past, but we can recover our entire history in order to do something for the present and hold hope for the future. We can be participants in our own history and decide what we will sow for tomorrow and sustain hope with our entire existence.

MS – You will represent Mexico at the Venice Biennale with Actos invisibles para sostener el universo, curated by Jessica Berlanga Taylor. How did you experience the invitation, and what challenges or transformations emerge when an intimate, embodied, and cosmologically rooted practice enters an international, institutional space like the Biennale?

RN – As we discussed earlier, our bodies inhabit different layers of reality at the same time. This does not apply only on a metaphorical plan – where we can employ Indigenous cosmologies to create contemporary art – but is also almost a defining characteristic of our existence as subjects shaped by the colonial historical process: we are always between two worlds, between what is our own and what is foreign, dancing together, interweaving, and becoming confused. Within our Westernised education, this caused us great anxiety – a kind of schizophrenia born of indeterminacy – until, in 2016, we met Felipe, a Rarámuri ritual specialist and the third governor of Huisarórare, Carichí, Chihuahua, who taught us one of the most important lessons of our lives. Felipe negotiated with the spiritual entities that were causing illness in his community; he negotiated with them through ritual, and at the same time he carried an INE (the Mexican national voter identification card issued by the National Electoral Institute) in order to negotiate with the chabochis (the Rarámuri term for all those who are not Rarámuri). He carried both with the same naturalness, ease, and sense of humor. From this encounter we understood and learned that everything is a political negotiation, and that when politics are practiced well, harmony can be generated between opposites, because what mattered most to Felipe was being able to heal, whether through ritual or through governmental, institutional bureaucratic procedures.

For us, participating in the Venice Biennale operates across multiple layers of reality at once: the intimate layer, of our relationship and our tribute to animic entities; the social layer, of proposing non-Western practices within the sphere of contemporary art; and the institutional layer, where negotiations take place around material possibilities and political power – always keeping as our guiding compass the importance of sharing the vitality and relevance of our Indigenous knowledge, as well as remembering and honouring the people who today safeguard, respect, and practice it. We seek to affirm that together we can all perform the invisible acts of building and practicing peace through non-patriarchal, non-colonial, non-classist, and non-racist forms.

MS – Mexico City is a place where ancestral layers, colonial histories, and contemporary realities intersect daily. Are there specific sites, routes, or rituals within the city that nourish your research and practice?

RN – Mexico City is one of the few cities where the layers of our country’s history remain visible within the architectural skin of the city itself. In the historic center, we can find the remains of the Templo Mayor, alongside the earliest colonial buildings, followed by modern and contemporary structures, all converging in a tide of movement generated between ancestral residents and those of us who have arrived, ancestrally, to inhabit and nourish the city, and to be nourished by it. Mexico City is our great Cipactli, our beloved Monster, that allows us to inhabit it and to traverse its ribs at the high cost paid by those who purchase the freedom of Mictlán and Tamoanchán together. The city has devoured and expelled us countless times, always offering a torrent of knowledge in its wake. The range of experiences and emotions that Mexico City can provoke is indescribably vast; at times it can be overwhelming and exhausting, yet in the darkest moments – when the forces of the necro-capitalist system crush us – our gods are there, whispering to us, speaking from behind the glass cases of the National Museum of Anthropology and History.