“New ancestral images”: Nicola Ricciardi interviews Maurizio Cattelan

Maurizio Cattelan

Nicola Ricciardi: Thinking back to “All” (2011), your retrospective at the Guggenheim – which in addition to collecting almost all of your works was accompanied by the affirmation that it would be your last exhibition – the words of Steve Martin come to mind. In 1981, after he had broken all public records over the previous three years, the comedian declared that he would never do standup comedy again because “It’s like painting the same blank canvas over and over and over and over and over. Once the concept is known, you don’t need to see two.” Steve Martin – who has since been a writer, actor, director, banjo player – has been true to his promise for 35 years, only to return to the stage in 2016. If we’re here to talk about your show at Pirelli HangarBicocca it’s because your self-imposed early retirement lasted a little less: what made you retrace your steps? And did you really believe that New York would be your last solo show?

Maurizio Cattelan: “All” was an incredible but very tiring and trying feat. I felt the need to get a taste of retirement, but the truth is that you don’t stop being who you are simply because you decide to and, after a while, my obsessions have come back to seek me out. Once rested – in a world where incredible things were happening – at one point I thought about returning. I was hoping to go more unnoticed.

For “All” you had assembled practically everything you had produced from 1989 up until then, filling the oculus of the Guggenheim rotunda to the bitter end. Today, in “Breath Ghosts Blind”, you present exclusively three works in a space that on the contrary appears almost completely empty – at least at first glance. How has your relationship with the exhibition space changed over the past ten years? “Less is more” – in the words of Mies van der Rohe?

I would not speak of a change of relationship with space, each space simply vibrates in a different way; it is not the first time that I have presented exhibitions with only a few works – thinking back to the one at the Kunsthaus in Bregenz in 2008 where there was only one work per floor, or my last Milanese rehearsal in 2010, at the Palazzo Reale. The truth is that the

void fills the space and that some works, under the right conditions, expand. “Breath Ghosts Blind” is an expanded exhibition, quite full i’d say. What’s more I am too old now to hang myself from the ceiling.

“Breath Ghosts Blind” is presented as “a three-act dramaturgy”. However, even more so than being at the theatre, I had the impression of being at the cinema. The works – illuminated by impeccable lights – appeared to me like scenes from a film (one example above all: Hitchook’s Birds). The same booklet accompanying the exhibition speaks of dark atmospheres reminiscent of the streets of the Ghotam City imagined by Tim Burton. Are you planning any forays into the world of cinema?

Cinema produces images and I constantly feed off images. It is my way of reading reality, my way of discovering what I don’t know, and also my way of getting bored with reality. The theatre fascinates me for its ability to compose paintings that breathe; cinema because it takes you away from your seat, but it is always an image. The light I chose for the exhibition is in fact a cinematographic light – it is no coincidence that I collaborated with the light designer and cinematographer Pasquale Mari – and the many cinematographic references that have been made about this exhibition (you have forgotten “2001. A Space Odyssey” by Stanley Kubrick) are right, but I would not consider them sought after or wanted, they are simply there, because they are now part of everyone’s memory and visual training. New ancestral images. For now, this is the only form of foraying.

If this exhibition were a film it would be a black and white film. Another peculiar aspect of the Pirelli HangarBicocca project is the restricted colour palette. We go from the immaculate white of “Breath” to the total black of “Blind” passing only through the hundreds of shades of grey of “Ghosts”. Not what one would expect from a Maurizio Cattelan exhibition (or film) – at least when compared to the work of the last ten years for Toilet Paper. Are you bored of colour?

Absolutely not! You should see the colour of my swimwear. And in any case, black and white are also colours.

Right. It could then be added that, in addition to black and white, it is also a silent film – or at least very silent, almost mystical-religious. In part I think it contributes to the fact that you arrive at your exhibition after passing through that of Neïl Beloufa, which certainly cannot be defined as laconic or austere. If you had to choose a soundtrack to accompany “Breath Ghosts Blind” what music would you choose?

Sometimes you think better in confusion, sometimes you need absolute silence. It’s all about controlling the distraction, pointing your thinking in the right direction. Many have traced this feeling of silence to a sort of sacredness that permeates the place and I cannot deny that the church effect is absolutely present. I would be curious to hear the echo produced by the sound in the spaces of the exhibition, but – as for the void – the sound would have a too cumbersome concreteness. There is not enough space for a fourth presence.

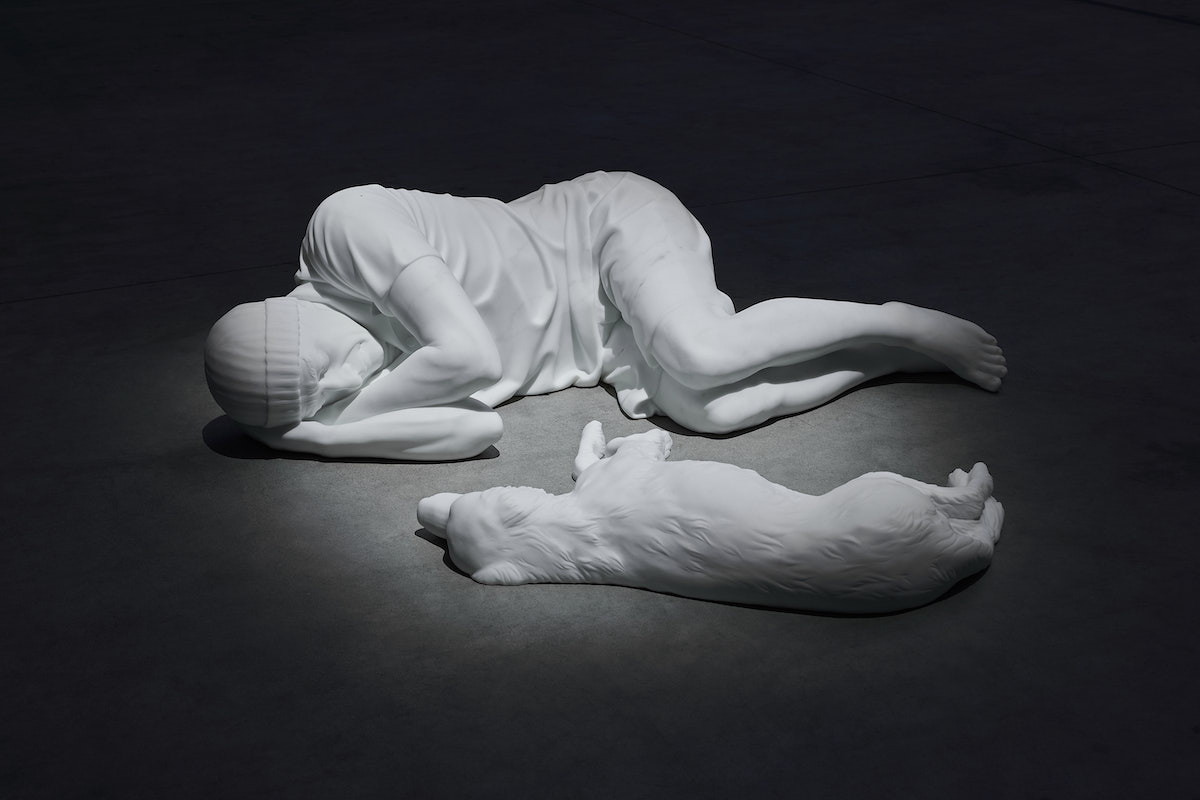

Let’s talk about the individual works. “Breath” is the sum of many recurring elements that have always crossed through your research: there is the reference to marble and classical sculpture, identification (is the man lying down you? Does he just resemble you? Does it matter?), the animal presence …current affairs permeate throughout the exhibiton, for example, the community of homeless people that swelled to excess during the pandemic (the media, even in Italy, put great emphasis on the case of Venice Beach). How much does the present moment play a role – or how much, on the contrary, does it aspire to be timeless and universal?

Art is always contemporary, timeless, political, personal, universal. If you do work that expires, it means it was not good enough and should be thrown away, like expired milk. Or you make yogurt out of it. Will it matter in a hundred years whether it’s me or not? It will be more important for people to wonder if the breath I’m talking about is still there. In the same way, the use of marble is interesting because in the material there is already a meaning and a value that seems overturned by the chosen subject. What is really negligible? What is noteworthy? This is what interests me, that people are still wondering about this a hundred years from now.

“Ghosts” is the third version of a piece that was already presented in 1997 (“Tourists”) and in 2011 (“Others”) in the corresponding Venice Biennales. However, this new representation could not be more of a contrast: if the Venetian pigeons – which appeared in full display and in contrast with works by other artists – could not help but steal a smile (even if only for the false promise to leave their excrements on the public of the Biennale), their Milanese cousins emerge from the shadows as menacing, hostile, ready to transform the aisles of Pirelli HangarBicocca Alfred Hitchcock’s Bodega Bay. It probably also affects the fact that we live in times when the pigeon is no longer seen only as a funny animal, but also potentially as a carrier of disease – a subject to which we are all inevitably more sensitive. Is this change of register and name (the tourists who have become ghosts) a reflection of the changing times? Or is it rather attributable to the change in the exhibition context?

Everything moves, everything changes and nothing is ever the same just because the eyes of the beholder have changed. The title is not necessarily in tune with what we see – sometimes, however, it is able to make the image visible, to make it hold more truth. If we accept the basic idea that an image should be “looked at” and not “read”, we should, by observing it, be able to recover all the information we need. But not only the art of the twentieth century, even the same classical painting of biblical myths and fables has taught us that this is not true. The title orientates our vision, delimits the horizon of the gaze, it is never an easy matter. I constantly wonder what might be capable of generating the right short circuit in the viewer – and this time “Ghosts” was the trigger.

Let’s talk now about “Blind”. The reference to the Twin Towers is quite explicit. When Eric Fischl presented his Tumbling Woman at Rockefeller Center in September 2002, in clear reference to the terrorist attack the year before, it wasn’t even a week before the work was covered up and then removed because it was deemed too emotionally charged – and, above all, “too soon”. In 2011, The New York Times ran a lengthy article claiming that in the United States, over ten years, there had been no truly revolutionary or ambitious cultural feats in response to 9/11 – as had been, for example, “Apocalypse Now”, in relation to the Vietnam War. Twenty years on (and over six thousand kilometres away) do you believe that art is now free to tackle that theme?

I have been thinking about this work for many years. Making it happen was in part the cure for a shock that left an indelible scar in the visual memory of anyone old enough to remember that moment. I still remember the very long way home from the airport (they had canceled all flights), but also the awareness that it would have been necessary to wait, in order not to risk appearing as a simple illustrator of the times. I understand that it may still seem too soon overseas, but I also think that twenty years and six thousand kilometres away was the right amount of distance. Art should always be free to face whatever it wants to, and deal with the consequences.

One of the cultural works that best translated post-9/11 anxiety is “Bleeding Edge” by Thomas Pynchon, a book that Jonatham Lethem has defined as “poetry of paranoia”. Personally I think it is a fitting definition also for “Breath Ghosts Blind”. If the paranoia is clearly visible – as an example, the thousand pigeon eyes staring at the viewer suffice – the poem is more hidden, but sensibly present in your exhibition (it is no coincidence that the review by il manifesto begins with the words “Poetically Unexpected”). I also read that you wanted to include the lines of a Syrian Kurdish poet, Golan Haji, in the exhibition catalogue. Can you tell me more about him and the choice to include him in your project?

Golan Haji has been working for some years on a book in which he analyses the figure of the dog and that of the beggar, comparing two fundamental poets of ancient literature, Homer and Al-Maarri (Arab poet of the I-II century AD), to these two figures. Among other things, both poets fit into the tradition of blind singers, whose works compose timeless metaphors. After millennia, dogs, beggars and the blind continue to maintain an incredible symbolic force. I didn’t say it though!

Last question. Death has always been a recurring theme in your artistic production, but in “Breath Ghosts Blind” it seems to emerge with even more force – partly because it is not counterbalanced by a playful moment, by a liberating laugh, as often happens in your work. It is also a not very Instagram-friendly exhibition, difficult to capture in images due to the marked physical and experiential component. For these two reasons I have heard many colleagues speak of “a serious exhibition”, of “a mature Cattelan”. Are they right? If we then consider that we live in difficult times, do you think that a certain degree of seriousness is appropriate or necessary today? Or that, on the contrary, and again to quote Steve Martin, an artist has the right if not the duty “to be absurd in a very serious time?”

If being mature only means being serious, I prefer to be considered the tall kid. Seriousness for me has to do with consistency – being consistent with oneself – and unfortunately (or fortunately?) I have never been able to be otherwise. So I don’t know whether to consider it good that for the first time someone thought I had matured; perhaps it should worry me instead! An artist first of all has the duty to be himself – otherwise why do it – and to be so completely, both when you are poetically paranoid and when you are playfully paranoid. And if the exhibition is not Instagram-friendly, well then patience: I have taken down my profile anyway!

Maurizio Cattelan’s “Breath Ghosts Blind” is on view at Pirelli HangarBicocca from July 15, 2021 to February 20, 2022.